“Framingham men have been among the first, the finest, the bravest…willing to endure personal sacrifice so that all may enjoy the liberties and freedoms that are ours today.” – Historian Tom A.C. Ellis1

From the colonial frontier to the jungles of Vietnam and the mountains of Afghanistan, Framingham’s gallant citizens have always answered the country’s call in times of peril. During the American Revolutionary War, they fought along Battle Road and on the battlefields of Bunker Hill, White Plains, Saratoga and beyond. The town’s contribution to the cause included the supreme sacrifice of at least twenty-seven of its citizens.2 Civil War Records indicate 530 of its men fought in that conflict. Most served in Massachusetts Volunteer infantry units. There were 52 fatalities, while another eighty-one were wounded in action.3 The town’s Civil War Hero, General George H. Gordon distinguished himself during the bloody Battle of Antietam in September of 1862. The city’s burial grounds and cemeteries also reveal the headstones of Spanish-American War Veterans. During World War I, Framingham’s Lieutenant Arthur R. Books downed 6 German aircraft earning him the coveted title of fighter Ace. World War II would see similar valor and unflinching sacrifice.

World War II was the defining event of the 20th Century. Global in scope and cataclysmic in its impact, the war gave rise to what has become known as the “Greatest Generation.” By the end of the war, the number of Framingham men and women in the services surpassed 3,000, including 200 women.4 Framingham News articles from 1943 claim the town had 500 men in the Army Air Corps of which 150 were commissioned pilots. Eighty-seven Framingham citizens made the ultimate sacrifice in WWII. On the home front, the planning, construction and operations of Cushing General Hospital were all nothing short of exemplary. Almost 14,000 soldiers were treated at that state of the art facility in less than two years. The people of Framingham played a central role in meeting the medical, therapeutic and spiritual needs of these wounded warriors. It was truly a community effort.

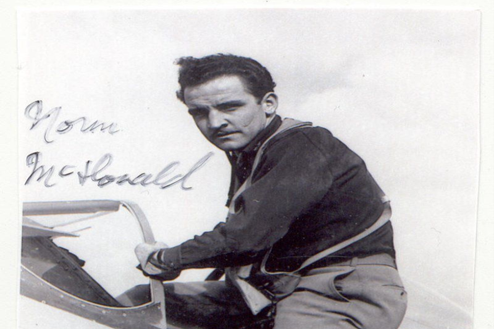

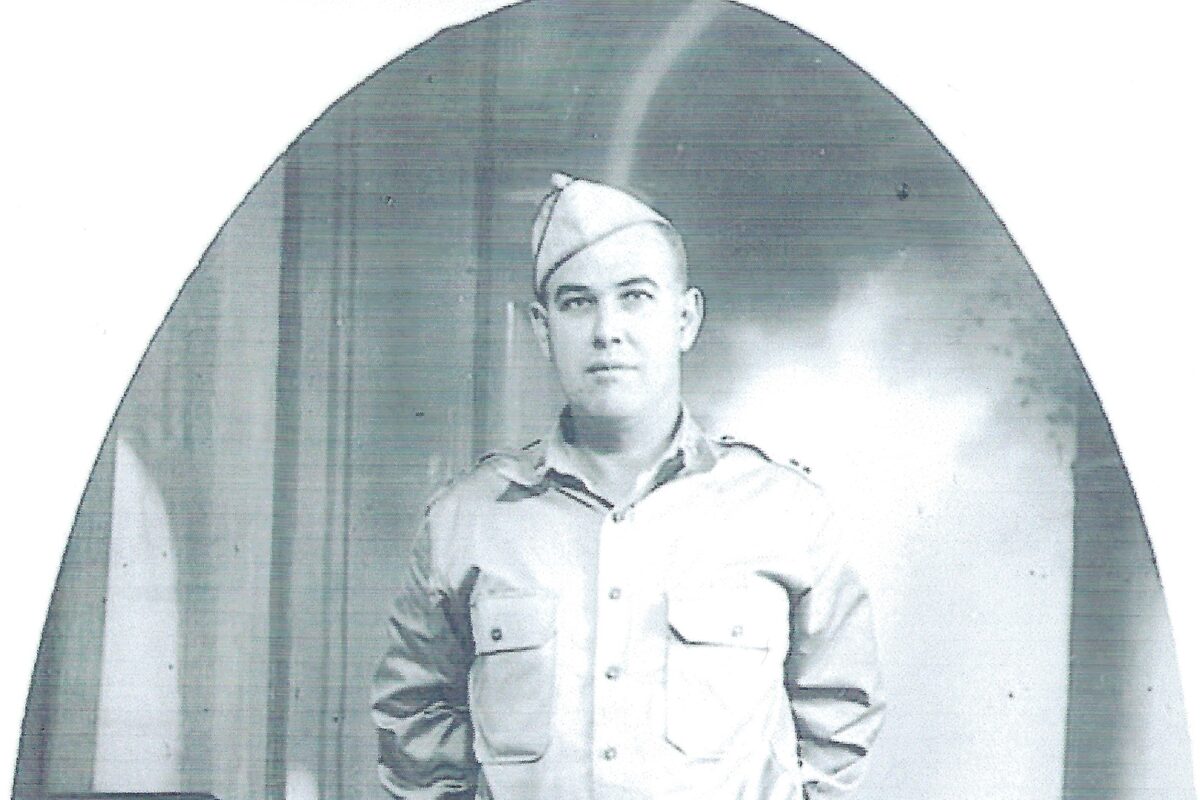

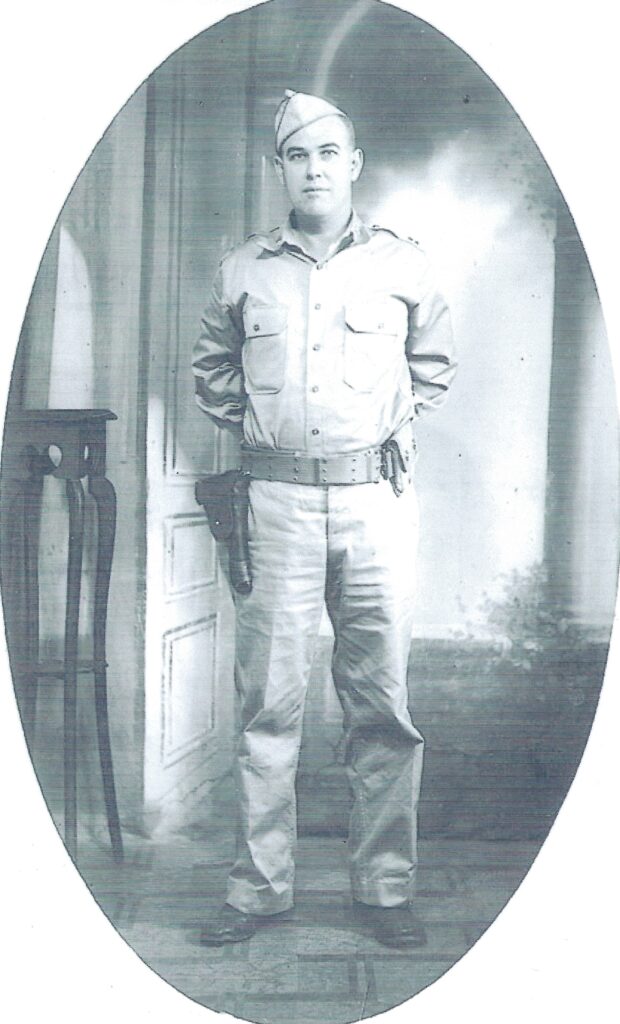

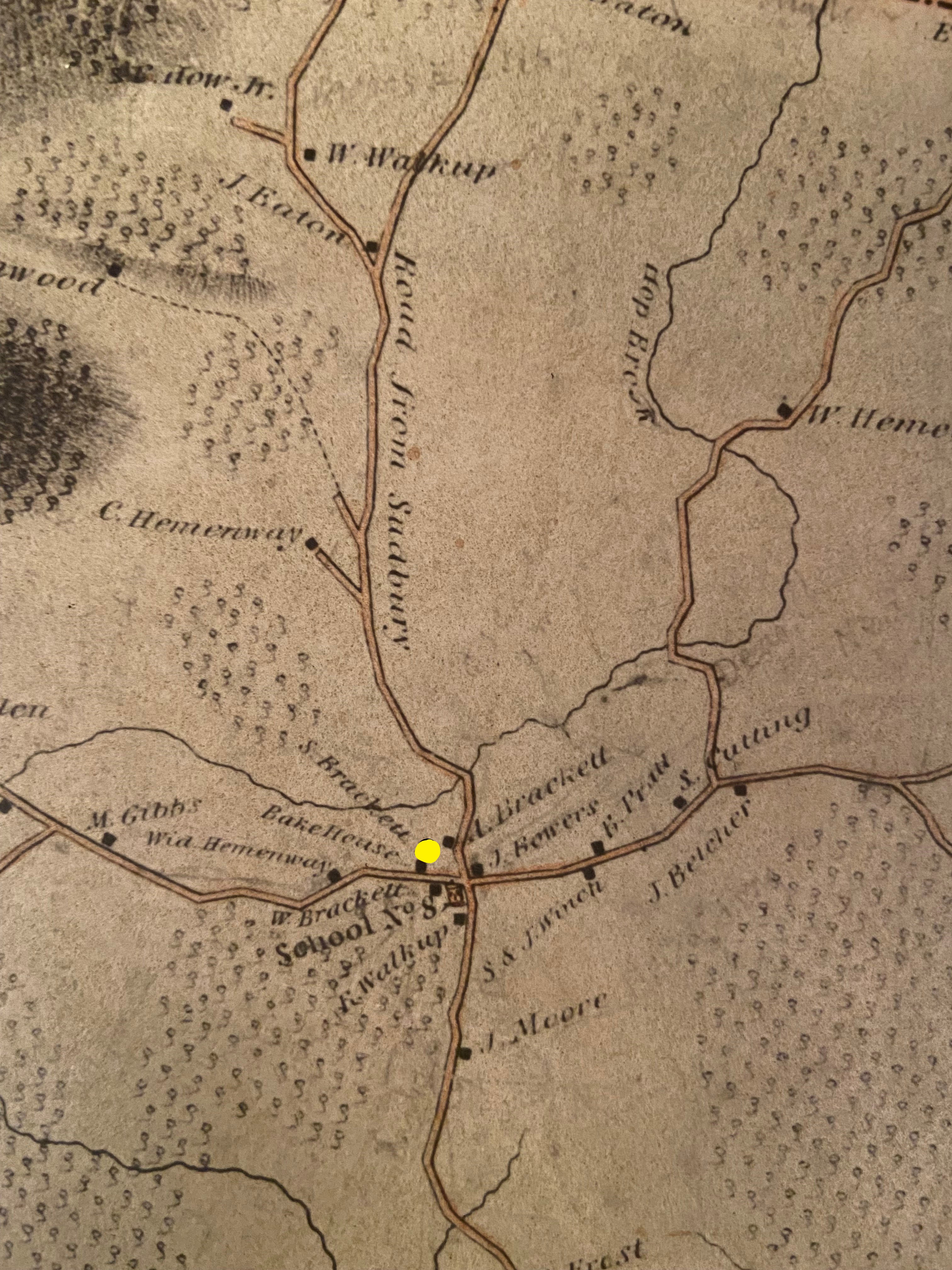

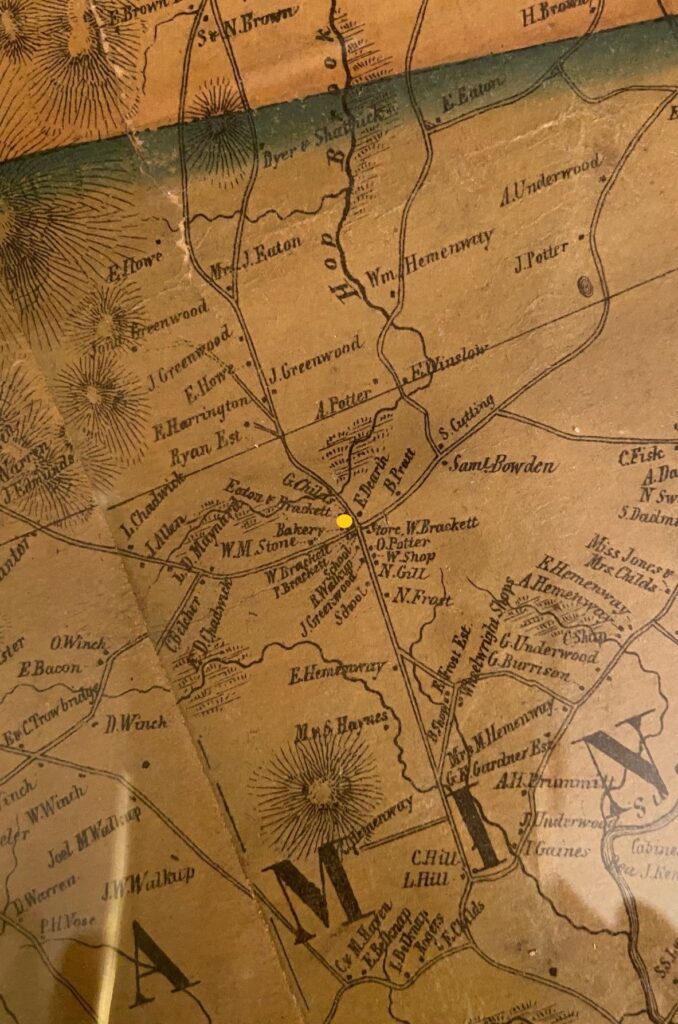

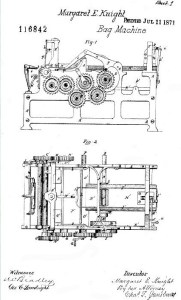

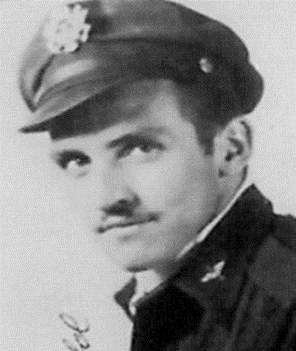

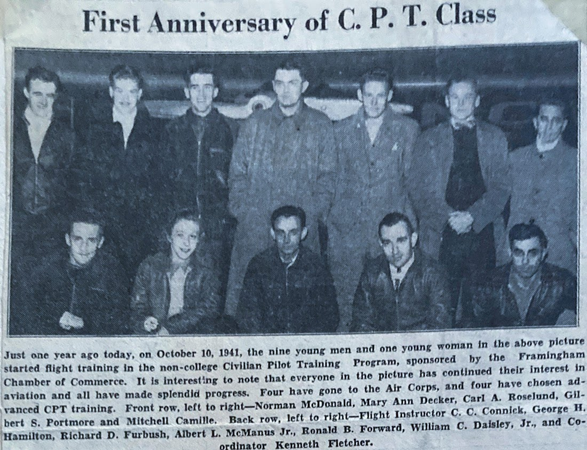

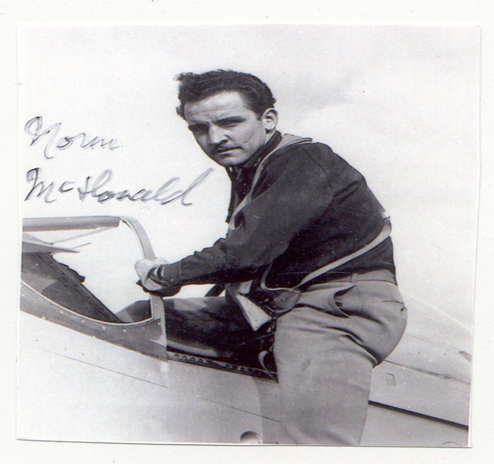

One of Framingham’s unsung WWII heroes was Lieutenant Colonel Norman Leroy McDonald of the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF). McDonald flew high performance fighter aircraft right up to the war’s end in Europe, amassing a total of 249 combat missions. Born in Framingham on January 21st in 1918, he lived at 13 Gorman Road (off Concord Street). He graduated from Framingham High School in 1935. He was a top athlete, playing football, baseball and hockey. Following graduation he attended the University of Carolina for one year, where he self-admitted to having majored in “Football.” He subsequently returned to Framingham where he was employed at Dennison Manufacturing. In 1940, Norm completed the U.S. Government funded Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) in Framingham. At that time, Framingham operated two airports and was the first town in Massachusetts to host CPTP. He attended the inaugural class on scholarship and was the first among his peers to solo from Framingham’s Gould’s Airport. Through this unique program, he received his Civilian Pilots License. According to the program’s mission statement, it was designed to “Revive the aviation industry, create a pool of pilots ready for military service, and develop a sense of airmindedness in the general population.” CPTP operated over 1,400 flight schools across the country. From 1939-1944, the program trained 435,165 aspiring aviators.5 Interestingly, the program was also open to African-Americans and women.

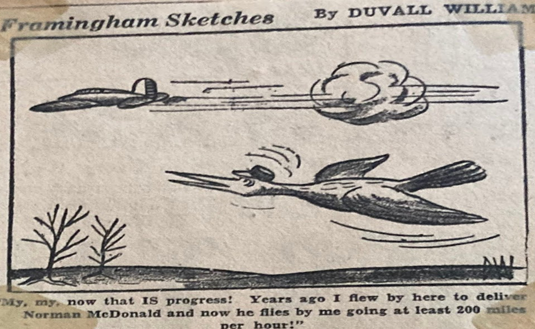

In April of 1941, Norm enlisted in the Army Flying Cadet Program. He was awarded his pilot wings in December of that same year (during the month the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor). He flew the P-39 Airacobra stateside prior to deploying to England with the 2nd Fighter Squadron. One of these flights even included a high speed, low altitude “buzzing” of downtown Framingham, the Dennison Factory, his home and the houses of his friends. Needless to say, he was the talk and toast of the town after this devilish stunt.

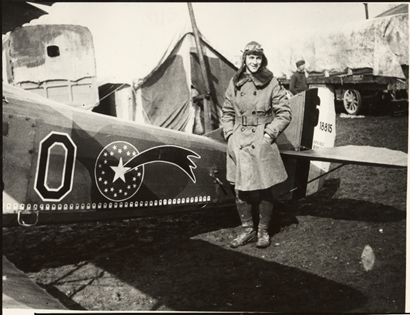

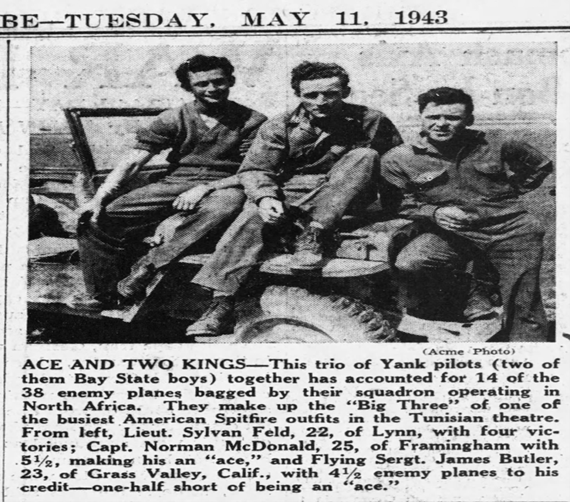

In the summer of 1942, the 52nd Fighter Group’s 2nd, 4th and 5th Fighter Squadrons transitioned to the sleek and elegant British Supermarine Spitfire. The British had convinced the U.S. (correctly so) that its P-39’s were not optimized for high-altitude, long range intercept and escort operations in western Europe, and instead furnished the 2nd, 4th and 5th with Spitfire Mark Vs. The Mark V was a more capable, next generation successor to the Spitfires that had defended England during the Battle of Britain. Under the watchful eyes of British instructors (including some with Battle of Britain experience), the three squadrons trained on the iconic fighter. In August of 1942, the 2nd Fighter Squadron (Norm’s unit) recorded its first combat mission (a convoy patrol) under the supervision of a Canadian Spitfire squadron.6 Additional European Theater operational activity was limited. In September, the Group was transferred to the XII Air Force in preparation for the Allied invasion of North Africa in November (Operation Torch) and the eventual Tunisian Campaign. The Allies were heading for the “soft underbelly” of Europe through North Africa, Sicily and the Italian mainland.

Facing unrelenting pressure, the Germans eventually surrendered North Africa on 13 May 1943. The next phase of Allied Mediterranean Operations began with the Invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) on 09 July 1943. Norm stayed with the 2nd Squadron throughout the North African and Sicily Campaigns. On 03 April 1943, Captain McDonald became an Ace with three victories on that day (5 required to achieve Ace status). He departed the Mediterranean Theater in October of 1943 for a stateside tour of duty (a training command). At that point in time, he had 7.5 confirmed aerial victories, making him one of the very few Americans to achieve Ace status in the British Spitfire – a very unique accomplishment. In fact, he was well on his way to double Ace status – 10 aerial victories. Of note, during World War II, less than 5% of all fighter pilots succeeded in shooting down five or more enemy planes.7 The American Fighter Aces Association (https://www.americanfighteraces.org/?v=d43cf049304b) maintains that of the thousands of WWII American fighter pilots trained and deployed for world wide combat operations, only 1,279 became fighter Aces. In fact, the same organization’s research has indicated there have been only 1,432 American Aces from 1916-1972. Of the 1,432, only 18% have reached the Double Ace milestone. Of the 21 WWII Aces from Norm’s 52nd Fighter Group, only 4 finished the war with Double Ace status (Norm and 3 other pilots). Norm was truly a member of an elite brotherhood.

Upon his return stateside, Norm was assigned as the Commanding Officer of a P-47 Thunderbolt training squadron at Bradley Field, Connecticut. While at home, he married Helen C. Maplebeck. Ms. Maplebeck was a member of the FHS Class of 1938. The best man for the 1944 McDonald-Maplebeck wedding was close friend Flight Sergeant Dick Neitz of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Dick, also a Framingham resident and FHS graduate, had gone north to fly Spitfires for the RCAF.

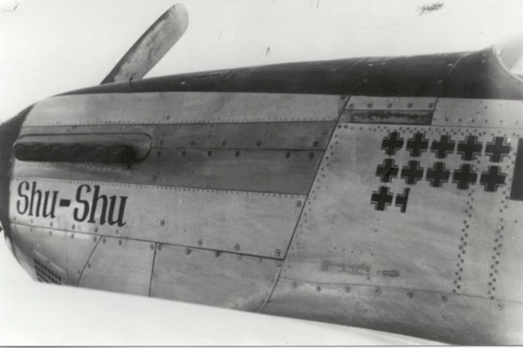

Shortly thereafter, Norm requested and was granted a second combat tour. He returned to Europe in August of 1944 where he joined the 325th Fighter Group’s, 318th Fighter Squadron. There he flew the long range, P-51 Mustang (primarily on bomber escort missions). Between November of 1944 and April of 1945, Norman chalked up 4 additional victories, bringing his total to 11.5. Having shot down 10 enemy aircraft, he had now reached Double Ace status. On 26 November 1944, Major Norman McDonald became Commanding Officer of the 318th Fighter Squadron. He retained this position until the war’s end in May of 1945. He would leave the service at the Lieutenant Colonel rank. For his valiant efforts, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (twice), the British Distinguished Flying Cross and the U.S. Air Medal (with 26 subsequent awards).

Norm returned to Framingham following his discharge in July of 1946. He quickly became a stalwart in the local business and real estate communities. He also continued to remain engaged in noteworthy public service and aggressively pursued civic volunteerism.

In 1947, Norm and 4 other local WWII Veterans (the founders of Allied Sports Association) purchased farmland adjacent to Route 9 in Westboro in order to build a race track for the increasingly popular sport of midget auto racing. The 55 acres were purchased for $100,000, which was a significant monetary investment (current value of approximately $1.3 million). The course was known as both Westboro Speedway or Westboro Sports Stadium. The track hosted over 9,000 people for its opening night on August 5, 1947. The facility operated, under multiple owners, from 1947 to 1985. The Westboro Plaza now sits on the speedway’s former Route 9 location.

Consistent with his enterprising spirit, Norm was an active member of the Framingham realtors community during a period of explosive, post-war population growth and its concomitant demand for affordable housing. He was a partner in Adams & McDonald Real Estate. He was also involved with real estate development on Cape Cod (Mashpee). Always entrepreneurial, he also purchased the Villa Restaurant in Wayland. For 17 years, he both owned and operated this iconic Italian restaurant.

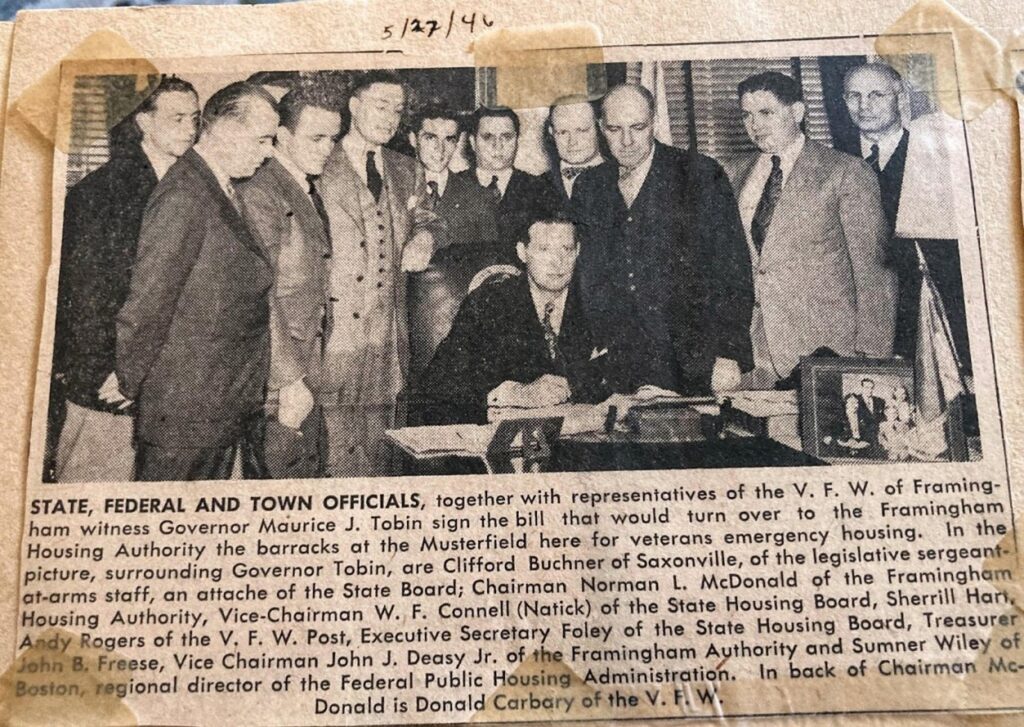

Equally compelling was the role now Mr. McDonald played in Framingham’s government, where he served as the Chairman of the Framingham Housing Authority. In 1947, he was instrumental in purchasing 52 acres of land from the state (the Muster Fields) for a Framingham Veterans Housing Project. Initially, these affordable units housed veterans and their families. Eventually, with the passage of time, the properties provided low income housing. In July of 1956, he presided over the ground breaking for a 24 unit, public housing project for elderly residents. His efforts in this area prompted longtime friend and Framingham Attorney Victor Galvani to state, “ He really did so much for Framingham. The Housing Authority really bailed out a lot of people and gave them a home when none were available.”8

As one might expect, Norm was also heavily engaged with a non-profit civic group. In his case, it was the Framingham Lions Club. Current and past members of the Lions refer to Norm as a “fixture” at almost all of their fundraising activities, including working in the Bowditch Field concession stand during high school football games. Volunteerism in support of humanitarian causes played a significant role in his world view.

Norman McDonald passed away on the 22nd of June 2002 in a Boston Hospital. He died from pneumonia following hospitalization after a concussion brought on by a fall. In accordance with his desires, and fully consistent with his life’s accomplishments and unique personality, his ashes were spread over Framingham from an airplane.

U.S Air Force General, fighter pilot and “Triple Ace” Robin Olds once said:

“Fighter pilot is an attitude. It is cockiness. It is aggressiveness. It is self-confidence. It is a streak of rebelliousness, and it is competitiveness. But there’s something else – there’s a spark. There’s a desire to be good. To do well; in the eyes of your peers, and in your own mind.”

By all accounts, Lieutenant Colonel Norman Leroy McDonald typified the attributes so succinctly described by Robin Olds. His post-war life and dedication to Framingham and its citizens also make him a shining example of what has been justifiably called the “Greatest Generation.”

Facts

- Norman Leroy Mc Donald was born in Framingham on January 21, 1918. He graduated from Framingham High School in 1935. He excelled in football, baseball and hockey.

- He participated in the federally funded Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) in Framingham, where he received his Civilian Pilots License. The Framingham Chamber of Commerce was the local sponsor.

- At the age of 22, Norm registered for the draft (October 16, 1940). He enlisted in the Army Flying Cadet Program on April 28, 1941. He was awarded his U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) Wings in December of 1941, the same month the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

- During WWII, Norm served with distinction, flying both British Spitfire and U.S. P-51 Mustang aircraft. He achieved 11.5 aerial victories giving him Double Ace status. He also commanded a P-51 squadron. He flew 249 total combat missions. In recognition of his bravery, aerial skills and leadership acumen, he was awarded 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFCs).

- After the war, he returned to Framingham and excelled in business (sports, real estate, restaurant) and local government (Chair of Framingham Housing Authority). He was a pillar of the community.

- Norm was the husband of Helen C. (Maplebeck) McDonald (1920-1968) and Helen M. Smith (1917-2008). Ms. Maplebeck was a member of the FHS Class of 1938. The best man for the 1944 McDonald-Maplebeck wedding was close friend Flight Sergeant Dick Neitz of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Dick, also a Framingham resident and FHS graduate, headed north to fly Spitfires for the RCAF. Dick would finish the war as an RCAF Warrant Officer. Upon his return to Framingham, he and his brother established “Lou’s Donuts” – a wholesale distributor selling to the Dennison Factory, the GM Plant, Hodgman Rubber and a number of smaller local businesses. Ultimately, Norm McDonald “showed him the real estate ropes,” which led to Neitz establishing Gateway Real Estate on Cape Cod. The real estate business continues today as Richard W. Neitz Real Estate in Yarmouth, MA.

- Norm was the father of three daughters.

To a Brave Man

McDonald is a grand old name

It fits you very nicely

In your Air Plane Game

Popping Stukas on the nose

Is no job where you can repose

You are sure doing your part

Keeping the Germans from getting too smart.

We here in Dennisons Busy Factory

Know your record is plus satisfactory

Having read of your valiant doings

And about Stukas blown to ruins

All America now knows your name

Captain Norman L. McDonald U.S.A. Air Force

And we are more than proud of you,

But here in Framingham

It’s Norman McDonald to you.

D.M. Hamblett

Boston Ordnance District

Inspector at Dennison Plant

*Provided by Sandra (McDonald) Ellis. Written circa mid-1943.

Norm McDonald’s WWII Confirmed Aerial Victories (11.5)

- 22 March 1943 – Two Junkers Ju-88 Multi-role aircraft (Spitfire)

- 01 April 1943 – 1/2 Ju-88 (victory shared with a second pilot) (Spitfire)

- 03 April 1943 – Three Junkers Ju-87 “Stuka” Ground Attack aircraft (Spitfire)

- 25 April 1943 – One Focke-Wulf Fw-190 Fighter aircraft (Spitfire)

- 01 August 1943 – One Dornier Do-17 Medium bomber (Spitfire)

- 05 November 1944 – One Messerschmitt Me-109 Fighter aircraft (Mustang)

- 02 April 1945 – Two Me-109 Fighter aircraft (Mustang)

- 10 April 1945 – One Me-109 Fighter aircraft (Mustang)

Bibliography

The American Beagle Squadron Association, A History of the Second Fighter Squadron in World War II, Author House, 2006.

Bruning, John R. Race of Aces, WWII’s Elite Airmen and the Epic Battle to Become Masters of the Sky, Hachette Books, 2020.

Contreras, Cesaro. “ ‘Filled to Capacity:’Westboro Speedway racetrack thrilled Metro West from 1947 to 1985”. MetroWest Daily News, 24 September 2021. https://www.metrowestdailynews.com/story/news/2021/09/24/remembering-westboro-speedway-from-1947-1985-westborough-ma-metrowest/8351021002/. Accessed 11 November 2023.

Hanelsen, Rob. “Framingham Loses a Flying, Fighting ‘Hero’”. MetroWest Daily News, 25 June 2002. p. A1.

Herring, Stephan W., Framingham An American Town, Framingham Historical Society, 2000.

Ivie, Tom and Ludwig, Paul, Spitfires and Yellow Tail Mustangs, Stackpole Books, 2005.

Plane & Pilot Magazine, “The History of the Civilian Pilot Training Program, Preparing Future WWII Pilots on a Massive Scale,” Plane & Pilot Newsletter, June 2022. https://www.planeandpilotmag.com/news/pilot-talk/the-history-of-the-civilian-pilot-training-program/.

Smith, Wallace L.”History of Framingham Airport 1929-1946.” Massachusetts Air and Space Museum,https://massairspace.org/virtualexhibit/vex11/3255958A-66A6-43C3-9507-823138890344.htm, Accessed 28 November 2023.

Wallace, Frederick A. , Pushing for Cushing in War and Peace, A History of Cushing Hospital 1943-1991, Damianos Publishing, 2015.

**Thanks to Mrs. Sandra Ellis (Norm’s daughter), Mr. Kirk Ellis (his grandson), Ms. Faith Jackson (his granddaughter), Framingham Lion’s Club members Peter Friel and Al Harrington and Mr. Dick Neitz of Yarmouth for the personal reflections and information they provided.

Notes

1. Stephan W. Herring, Framingham An American Town (Framingham, 2000), 172.

2. Ibid., 95.

3. Ibid., 173.

4. Ibid., 286.

5. Cassie Peterson, “The History of the Civilian Pilot Training Program, Preparing Future WWII Pilots on a Massive Scale,” Plane and Pilot Newsletter, June 3, 2022, https://www.planeandpilotmag.com/news/pilot-talk/the-history-of-the-civilian-pilot-training-program/.

6. Tom Ivie and Paul Ludwig, Spitfires and Yellow Tail Mustangs (Mechanicsburg, 2005), 11.

7. John R. Bruning, Race of Aces, WWII’s Elite Airmen and the Epic Battle to Become Masters of the Sky (New York, NY, 2020), x.

8. Rob Hanelsen, “Framingham Loses a Flying, Fighting ‘Hero’”, MetroWest Daily News, 25 June 2002.

Suggested Videos

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U9QBz1bYqhg America’s WW2 British Planes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UJYoplgjzt8 P-39 Airacobra

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3hzI81kEUFo Spitfire

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0MAv1CHDy8 P-51D Mustang