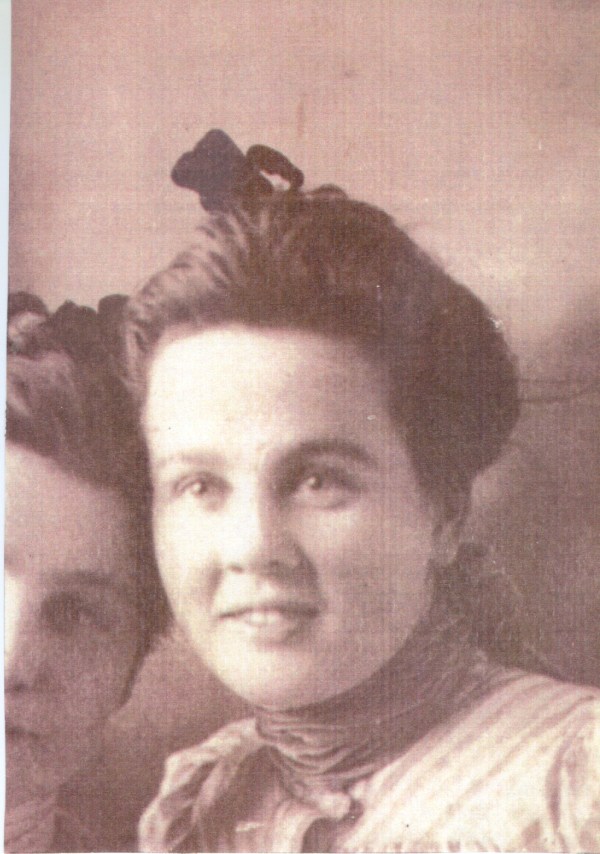

Josephine Collins (1879 – 1960) is best remembered as an activist fighting for woman’s right to vote. Born in 1879, she was the oldest daughter in a large Irish family that lived on Salem End Road in Framingham.

There are few details describing her early life. She grew up at a time in which women had fewer opportunities than men. Women were not able to vote, hold public office, or enter into legal contracts. They were also deprived of equal educational and employment opportunities. Although Josephine was a single woman and her opportunities were limited, she found many ways to support herself. For a time, she cared for a Rhode Island minister’s family. She also worked at Collin’s Market, a family business in Framingham Centre. While her brother, John, served in World War I, Josephine took over the management of this market.

Josephine was a successful businesswoman in her own right. She opened up a Tea Room on the corner of Pleasant Street and Belknap Road; a dry goods shop; and her own Periodical’s Shop in South Framingham’s Esty Building. In her later years, Josephine worked as a bookkeeper for Babson College.

In the mid 1800’s, women began to demand the right to vote which led to the formation of the woman’s suffrage movement. During this time, two national suffrage organizations were established, one by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the other by Lucy Stone. These two groups eventually merged and focused their energies on a state by state campaign for woman’s voting rights. In 1916, Alice Paul established the National Woman’s Party (NWP). The newly formed NWP lobbied for the passage of an amendment to the United States Constitution for national suffrage. It was this organization that Josephine joined in 1918.

On February 24, 1919, women were called to rally on Boston Common to greet President Woodrow Wilson who was on his way to Washington D. C. from the World War I peace talks in Versailles. Josephine attended this rally which protested the President’s failure to take a stand on suffrage. The group held signs demanding the passage of the suffrage amendment. Josephine held a sign that read: “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” The police warned the women that they might be arrested if they did not disperse. Twenty-two women including Josephine were arrested and taken to the House of Detention for Women. Josephine was part of a group who refused to give the court their real names and to pay the five dollar fine. This group was then taken to the Charles Street Jail to fulfill their eight day jail sentence. Much to Josephine’s chagrin, one of her brothers paid her fine and she was released from jail before she served her full sentence, though she was not pardoned.

Upon her return to Framingham, she resumed business at the dry good shop and continued to support the cause of woman’s suffrage. Unfortunately, business suffered financially due to her involvement in the suffrage movement. Many husbands prohibited their wives from frequenting her shop.

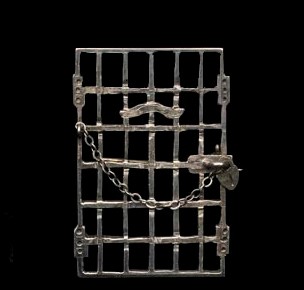

Alice Paul, the founder of the National Woman’s Party, chose to honor the women who were jailed in the Boston and the Washington D. C. suffragist rallies. A pin depicting a jail house door, which she designed, was given to each of these eighty-nine brave suffragists at the National Woman’s Party December 9, 1917 meeting in Washington, D. C. Of all the pins awarded that day, only five are known to have survived. The pins of Josephine Collins and Louise Parker Mayo are in the collection of The Framingham History Center.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution giving women the right to vote was ratified in August 1920. On the eighty-fifth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Town of Framingham dedicated a square to honor the two local women, Josephine Collins and Louise Parker Mayo, who fought so long and hard for its passage. Mayo-Collins Square is located at the corner of Oak Street and Edgell Road.

Facts

Josephine Collins died May 1, 1960 at Cushing Hospital

Her family called her Aunt Jo

Siblings: 1 sister and 5 brothers

Further Reading

Gillmore, Inez Haynes. The Story of the Woman’s Party. Harcourt, Brace, 1921. Internet Archives. https://archive.org/details/cu31924030480556 Accessed 04 Sept. 2017.

McCully, Emily Arnold. The Ballot Box. Knopf, 1996.

National Woman’s Party. http://nationalwomansparty.org/learn/national-womans-party/ Accessed 22 Aug. 2017.

Bibliography

Danker, Anita C. “The Grassroots Suffragists: Josephine Collins and Louise Mayo, a study in Contrasts.” New England Journal of History, vol. 67, no. 2, Spring 2011, pp. 54-72.

Spitz, Julia. “90 Years Ago Women Gained the Right to Vote.” MetroWest Daily News 22, Aug. 2010. http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/article/20100822/NEWS/308229967 Accessed 04 Sept. 2017.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. Boni and Liveright, 1920. Internet Archives. https://archive.org/details/jailedforfreedo00stevgoog Accessed 22 Aug. 2017.