Meta Warrick Fuller (1877 – 1968) is an important figure for a wide array of people. As a female artist of color, she broke down gender and racial barriers despite adversity and discrimination. Born in Philadelphia in 1877, Meta’s father was a barber who would go on to become a successful caterer, and her mother was a successful beautician with many upper class clients. Meta was exposed to art from a young age as she took dancing lessons and frequently went to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Her talents were evident early on and she won a three year scholarship to the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art. Afterwards she went on to two years of post graduate study in Paris starting in 1899, after convincing her worried yet supportive parents it was the right thing for her to do.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

While in Paris, she visited the famed sculptor Auguste Rodin, known best for his piece The Thinker. Rodin praised Meta’s sculptures and she was able to sell some of her work, bringing her the notoriety and the money she needed to keep working. She would also meet another friend in Paris, William E.B. DuBois, an influential Black author, historian and civil rights activist. He would later come visit her in her Framingham home.

Meta returned to Philadelphia in 1902 and exhibited her work at prestigious institutions. She accepted a U. S. government commission to create dioramas illustrating events in African-American history for the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition, yet she was snubbed by the local artist community because of her race and gender. In 1910, she lost her tools and sixteen years worth of paintings and sculpture in a Philadelphia warehouse fire. By the 1920s Meta had met and married Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, a leading psychiatrist who would also come to be known for his work with Alzheimer’s Disease. The couple bought a house on Warren Road in Framingham and had three children. Their home would be a lively part of the community as many prominent people of color came to visit, including the Prince of Siam.

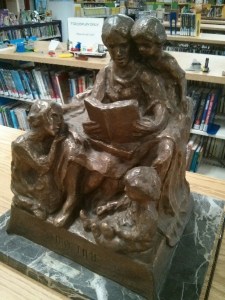

Overcoming prejudice and the expectation that she would give up her career to raise her children, Meta continued to work on her art. Her sculptures are very diverse – some have religious themes, deal with slavery and prejudice, or depict death, grief and sorrow. Others draw on the music and folk tales of her African ancestry for inspiration. Meta was heavily involved with St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church and helped to organize the Framingham Dramatic Society. She would dance, direct, produce, and make costumes for various productions. Meta wrote poetry that reflected her life, and passed away in 1968 at the age of 91. Despite being faced with sexism and racism , Meta’s genius shone throughout her life and work as she carried herself with pride and dignity that is evident in her timeless pieces of art which are now displayed in various places around the U.S.

Bibliography

Ater, Renee, “Making History; Meta Warrick Fuller’s “Ethiopia.”” American Art, vol 17, no. 3, 2003, pp. 12-31. Academia http://www.academia.edu/26577999/Making_History_Meta_Warrick_Fullers_Ethiopia_

Ater, Renee. Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller. University of California, Berkley, 2011.

Herring, Stephen W., Framingham: An American Town. The Framingham Historical Society, 2000.

Hirschler, Erica E. Studio of Her Own: Woman Artists in Boston, 1870-1940. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 2001.

An Independent Woman. The Life and Art of Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968). Danforth Museum of Art, 1984. Accessed 6 Apr. 2017. offile:///C:/Users/janew/AppData/Local/Microsoft/Windows/INetCache/IE/E1IIJYW0/meta_fuller_catalog_1984-5.pdf

Koontz, Shonnette, A Collection of the Life and Work of Meta Vaux Fuller, 1877-1968. Institute West Virginia, 2003.

Patton, Sharon E. African American Art. Oxford University Press, 1998.