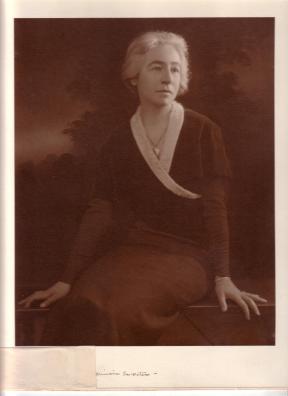

Miriam Van Waters (1887-1974) was a noted progressive American social worker, penal reformer, and prison director. She grew up in Portland Oregon, the eldest daughter of a liberal Episcopal minister. Van Waters graduated from the University of Oregon in 1910 with an M.A. in psychology. She then went on to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. During the summer of 1912, she worked on a project where she collected and studies data on delinquent girls at the Portland Municipal Court in Oregon. This experience not only helped Miriam prepare her doctoral thesis, but became an inspiration for her life’s work.

Upon graduation from Clark in the spring of 1913, Miriam was hired as a special agent for the Boston Children’s Aid Society. She was in charge of young girls brought before Judge Harvey H. Baker, 1st Judge of the Boston Juvenile Court. While attending hearings, she saw that Judge Baker made every effort to save children and keep them out of jail. This approach deeply touched, and influenced Miriam. In April of 1914, she accepted the job of Superintendent of the Frazier Detention Home in Portland, Oregon. Miriam found the conditions at Frazier deplorable. She immediately began to make the following improvements: (1) she segregated the sick children from the healthy ones; (2) hospitalized the seriously ill; (3) cleaned the facility; (4) established a library; (5) hired a visiting doctor, resident nurse, recreation director, and a dietitian. Miriam gradually eliminated corporal punishment, and organized work, play, and schooling for every child. All the children were tested. Those who required specialized care were transferred to appropriate institutions. These reforms favoring education and rehabilitation over punishment were to be the hallmark of her approach to prison management.

In the winter of 1915, Miriam was diagnosed with tuberculosis. This forced her to give up social work while she recuperated. In 1917, her health was sufficiently restored, she move to California where she accepted the position of superintendent of Juvenile Hall in Los Angeles. Miriam found Juvenile Hall to be grossly mismanaged. Within four months, she replaced the majority of the staff, hired a resident nurse, and established a dental clinic and a psychological lab. In 1919, she founded El Retiro, a new residential high school for delinquent girls aged fourteen to nineteen years. Miriam envisioned her school with a homelike, nourishing atmosphere; a positive place for growth, where girls could be successfully returned to society.

Throughout her career, Miriam had the financial and political support of many wealthy, influential people including Eleanor Roosevelt, a first lady, Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard Law professor, Ethel Sturges Dummer, a Chicago philanthropist, and Geraldine Morgan Thompson, a feminist social reform pioneer from New Jersey among others. Geraldine and Miriam maintained a close personal relationship for forty years.

In the early 1920s, Miriam obtained a grant from Ethel Sturges Dummer to conduct a survey of industrial training schools and reformatories for girls across the United States. This study, published in 1922, included programs that Miriam felt would point a young girl in the right direction as well as her observations of the institutional facilities she visited. While in Los Angeles, Miriam also wrote two books on juvenile delinquency: Youth in Conflict (1925) and Parents on Probation (1928). In 1926, Miriam was drawn into national service. While maintaining her positions in Los Angeles, she was appointed to manage the juvenile delinquency segment of the Harvard Law School Crime Survey. This survey sought to discover the causes of crime and the best ways to prevent it. She also began working as a consultant on juvenile delinquency for the Wickersham Commission established by President Herbert Hoover from 1928-1931.

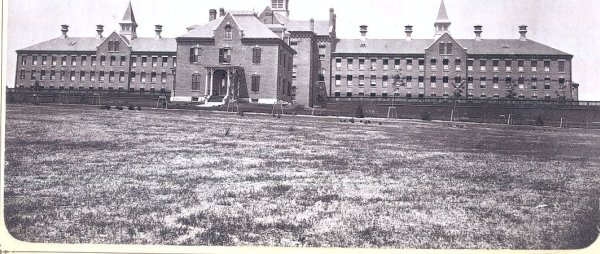

In the early 1930s, Miriam’s reputation was growing nationally, while in Los Angeles it was declining. Many there thought her methods too liberal. She left El Retiro in 1927 and resigned from the Los Angeles Juvenile Court on November 11, 1930. The next year, she relocated permanently to the East coast. In 1932, she accepted the job as superintendent of the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women at Framingham. A position she would hold for the next twenty-five years.

At Framingham, Van Waters continued to build on the progressive agenda of Jessie Donaldson Hodder, the previous superintendent. Miriam’s goal was to make each student, as she called those sentenced to Framingham, feel as if the entire staff worked on their behalf to better them and to prepare them for their eventual release back into society. She immediately began changing the environment of the Reformatory. Within a year, she replaced the bars on the windows with curtains, and instituted a cottage system of housing for select groups of women. The Hodder Hall, for girls age seventeen to twenty-one years, was an effort to keep them away from the more hardened and older women. The Wilson Cottage was for mothers and babies. Here, the women learned to care for their babies with the help of nurses, doctors, and psychiatrists. Each new baby born to one of Miriam’s students received an engraved silver cup from “Aunt Miriam.”

Miriam encouraged members of the community to volunteer at the prison, including local students, college professors, clergy, and a variety women’s groups. Many of these volunteers taught classes on current events, psychology and the arts. She also brought in counselors and therapists. Miriam went on to form many clubs at the reformatory, sixteen of them at one point. The purpose of the clubs was to offer more constructive outlets for her students. She also, expanded the opportunities for students to learn job skills by working outside the Reformatory. These included not only domestic work, kitchen helpers, and hospital maids, but also jobs at some local businesses and industries as well.

Following the end of World War II, the political winds changed. The liberalism of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal was replaced with conservatism. Liberals such as Van Waters came under close scrutiny. In 1948, the new Commissioner of Corrections, Elliot McDowell and his deputy, Frank Dwyer, launched an investigation into reports of homosexuality at Framingham Reformatory for Women following the suicide of a student. McDowell also challenged her expanded indenture program and excursions outside the Reformatory by inmates to medical appointments and movies. In January 1949, McDowell fired Van Waters.

Van Waters appealed her firing. Her appeal hearing began on January 13, 1949 with McDowell presiding. After eighteen days of examination and cross-examination, McDowell stayed with his original decision to fire her. Van Waters appealed to Governor Paul Dever for a re-hearing which he granted. The re-hearing began on March 4 and ended on March 11 with a reversal of McDowell’s decision. Van Waters was reinstated as Superintendent. However, for the rest of her career, her reforms were closely monitored by the state, and most did not survive for future generations of inmates sent to the Framingham Reformatory.

Miriam Van Waters retired in 1957 after a period of declining health. She moved into a home in Framingham with two former inmates. Through correspondence and letters to editors, she continued to support prison reform and social justice issues. Van Waters died of a stroke at her home in 1974. She was buried in Sherborn at the Pine Hill Cemetery overlooking the Framingham Reformatory for Women.

Miriam Van Waters never married. She did however adopt Betty Jean Martin, a seven year old girl, in 1932. Van Waters renamed the girl Sarah Ann Van Waters. Sarah Ann was educated at the Putney School in Vermont, 1936-1939, Swarthmore, 1939-1941, University of New Hampshire, 1941-1943. While at New Hampshire, she met and fell in love with Richard Hildebrandt. The couple soon married, settled in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, and had three sons. After several years, they divorced and Sarah eventually moved to Framingham to live with her mother. On February 6, 1953, Sarah died following a car accident on an icy road. She was only 30 years old. Sarah Ann is buried in the Pine Hill Cemetery near her mother.

Facts

Mother: Maude Ophelia Vosburg Van Waters, 1866-1948

Siblings: Rachel Van Waters, 1885-1887; Ruth Van Waters Burton, 1893-1967; George Vosburg Van Waters, 1899-1981; Ralph Orin Van Waters, 1904-1989

Children: Sarah Ann Van Waters Hildebrandt, December. 22,1922-February 6,1953, adopted

Clubs formed by Van Waters at the Framingham Reformatory:

Harmony News: in-house newspaper

Two-Side Club: to teach the democratic process of government

Merry Makers: all black group for music and drama

Social Club: games and cards

Dorothy Dix Club: to study the democratic process

Audubon Club: conservation of natural resources

Camp Fire Girls

A.A.

Sports Club: sponsored softball, archery and basketball teams

Glee Club: musical performances

Birthday Club: met monthly at the Superintendent’s home to celebrate student birthdays

Drama Club: staged plays

Maud Ophelia Club: for the elderly students

Rangers Club: nature club

Parole Club: to prepare women for life on the outside

Poetry Club: to read and write poetry

Tumblers Club

Bibliography

Bosworth, Mary, ed. Encyclopedia of Prisons and Correctional Facilities. Sage Publications, 2005.

“Celebrating the Quasquicentennial of Miriam Van Waters (October 4, 1887-January 17, 1974).” Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study Harvard University. Posted October 4, 2012. https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/schlesinger-library/blog/celebrating-quasquicentennial-miriam-van-waters-october-4-1887january-17 Accessed 22 Jan. 2019.

Freedman, Estelle B. “Miriam Van Waters.” Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History in America, edited by Marc Stein, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004. Biography In Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K3403600520/BICu=fpl&sid=BIC&xid=50576d17. Accessed 28 Jan. 2019.

Freedman, Estelle B. “ Separatism Revisited: Women’s Institutions, Social Reform, and the Career of Miriam Van Waters.” Kerber, Linda K., ed. U. S. History as Women’s History: New Feminist Essays. University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

“Miriam Van Waters.” Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/145138388/miriam-van_waters Accessed 27 Jan. 2018.

“Motor Crash Kills Adopted Daughter of Dr. Van Waters.” Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960), Feb 07, 1953, pp. 21. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/docview/839982423?accountid=9675. Accessed 27 Jan. 2019.

Rowles, Burton J. The Lady at Box 99, the Story of Miriam Van Waters. Seabury Press, 1962.

Photo of Miriam Van Waters. Framingham History Center Collections.