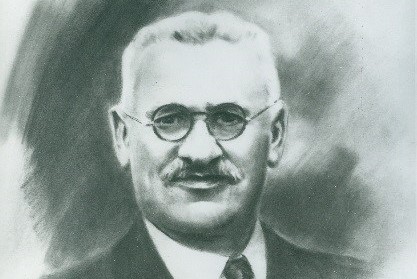

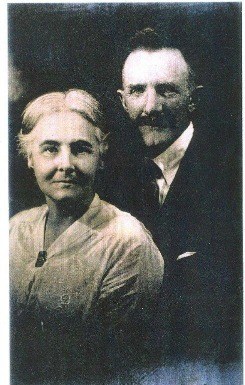

Bonfiglio Perini (1863(?)-1924), an Italian immigrant, through hard work and sharp business sense became an American success story. He was born in 1863(?) in Gotolengo, Italy. When he was a young boy, he began working as a gardener for the Rothschild family in Switzerland. In 1882 at the age of nineteen, he returned to Italy to serve in the military. It was during this time that he dreamt of coming to America. After completing his military service, Bonfiglio began his journey to America. He went first to France where he had to work for a year and a half to earn enough money to pay for the rest of his passage. He arrived in New York in 1885.

By 1887, Bonfiglio had made his way from New York to Massachusetts where there was plenty of work building dams. In 1890, he met and married Clementina Marchesi in Boston. The couple settled in Ashland, Massachusetts to raise their large family. Around 1894, Bonfiglio established his own general contracting company in a storefront in Ashland. In the early years, the company built waterworks projects, such as dams and culverts, and sections of the Boston and Worcester Railway in Eastern Massachusetts. During these years, he had a following of Italian craftsmen who worked with him on his projects. Bonfiglio was an innovator who looked beyond the excavation equipment of the day (horses and tipcarts) to mechanized equipment (steam shovels, etc.). His company soon earned a reputation for high quality work and was offered jobs throughout New England and New York. In 1917, Bonfiglio incorporated the company and renamed it B. Perini & Sons, Inc.

In 1917, they built one of the first hot-mix asphalt roads in Rhode Island. During the 1920s, B. Perini & Sons worked mostly on highway projects, including relocating a section of the Boston Post Road (Route 20) in Sudbury paid for by Henry Ford and the Wayside Inn.

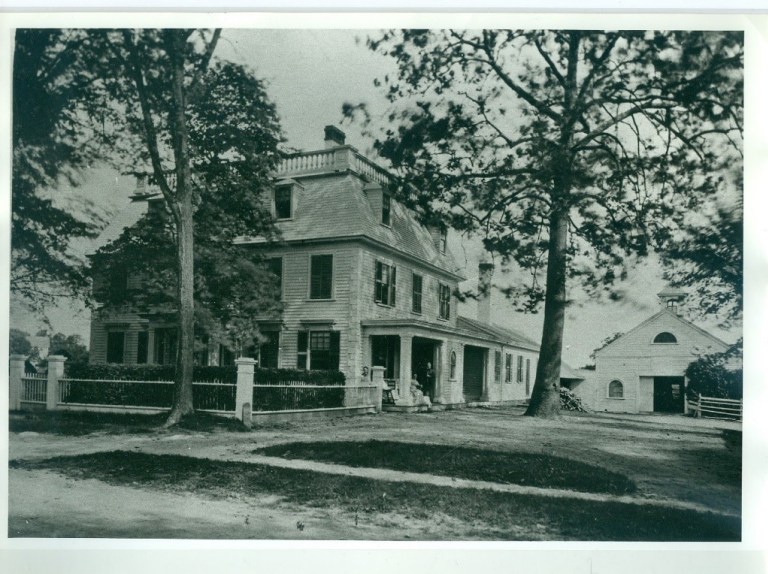

When Bonfiglio died in 1924, four of his children took over running the company: Louis (age 21) became President, Joseph (age 24) became Treasurer, Ida (age 28) became Secretary, and Charlie (age 14) became Vice-President of Equipment. Under their leadership, the company continued to grow. In 1931, they moved their offices from the Ashland storefront to a new building on Mount Wayte Avenue in Framingham (across from Bowditch Field).

Over the years, the Perinis have been involved in many different business ventures. During World War II with the demand for coal great, they went into the coal strip-mining business while working in several coal belt states. For a time, this proved to be a very profitable business. By 1948 with the war over, demand for coal dropped off and the Perinis shut down this part of their enterprise. In 1945, Louis Perini and two other investors purchased the Boston Braves Major League Baseball Team. The Perini Corporation eventually bought out the other investors and moved the team in Milwaukee in 1953. The Perinis owned the team until 1961.

The 1950s saw many changes. The company was renamed the Perini Corporation, they started a building division, and they took on projects worldwide. Locally, they built three middle schools in Framingham (Barbieri, Cameron, and Farley), Framingham Industrial Park, as well as a sewer treatment plant in Marlborough. They worked on pipelines in Alaska and Saudi Arabia, built a hospital in Kuwait, and worked on subway systems in San Francisco and Toronto. In Massachusetts, they worked on the Callahan Tunnel, Copley Place, the Big Dig, Massachusetts Turnpike, Cape Cod Canal, and runways and buildings at Logan Airport.

Perini Corporation merged with Tutor-Saliba Corporation of California in 1997 and today is known as the Tutor-Perini Corporation. In October 2001, Tutor-Perini moved its world headquarters out of Framingham to southern California.

Bibliography

Bisha, Pat A. “Perini Corporation: A Family Affair.” The MetroWest Business Review, Sept. 1986, p.8+

Brauer, Steve. “The Perini’s.” South Middlesex News, 01 June 1975, p. 81H.

Field, Charles Jr. “Perini History Part 1 (1885-1997).” Youtube. 18 Dec. 2014. https://youtu.be/jfRw50CVhTg Accessed 27 June 2017.

Patterson, Charles J. “The Perini Story.” America’s Builders 24, 1954:18.

“Perini Corporation History.” Funding Universe. 11 Apr. 2017.

Tremblay, Bob. “Framingham’s Perini Corp. builds on history.” Metro West Daily News, 13 July 2009. http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/x737770421/Framinghams-Perini-Corp-builds-on-history. Accessed 27 June 2017.

Tutor Perini Construction to leave Framingham Following Merger.” Boston.com, 21 Oct. 2009. http://archive.boston.com/yourtown/news/framingham/2009/10/tutor_perini_construction_to_l.html Accessed 11 Apr. 2017.