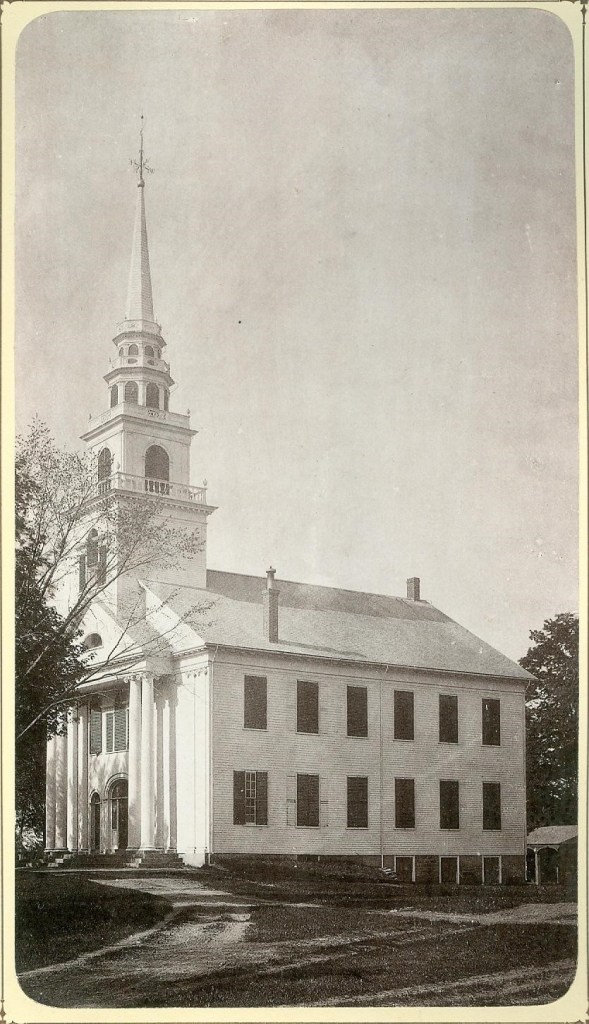

Nevins Hall …. We’ve all been there, perhaps to attend a town meeting, a holiday concert, a wedding, or a prom. In 1994, President Bill Clinton gave a speech there, and in 2016, author David McCullough capped off “Framingham Reads Together” with a talk about his book The Wright Brothers. Political debates and early voting also have taken place in this space. Ever wonder how it got its name?

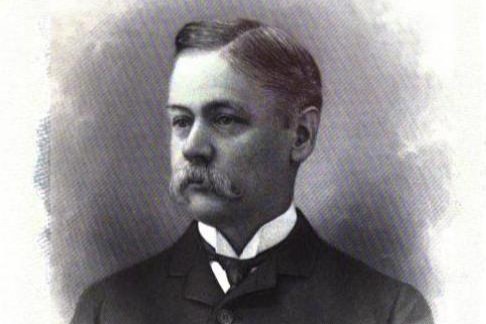

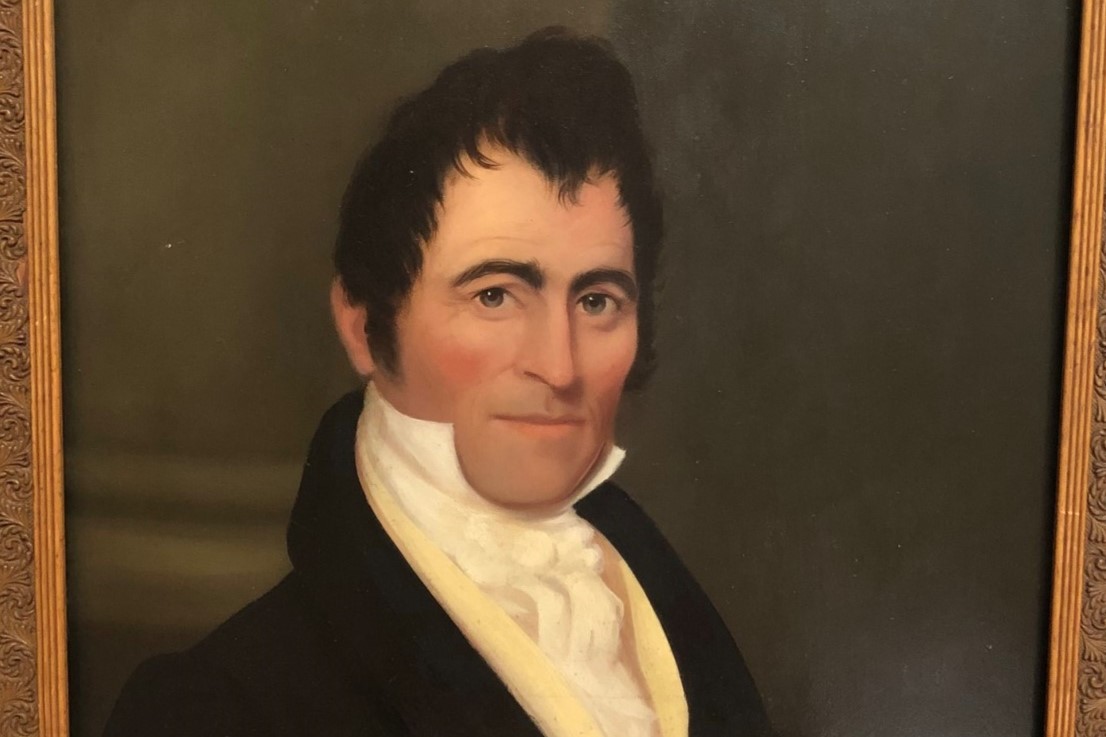

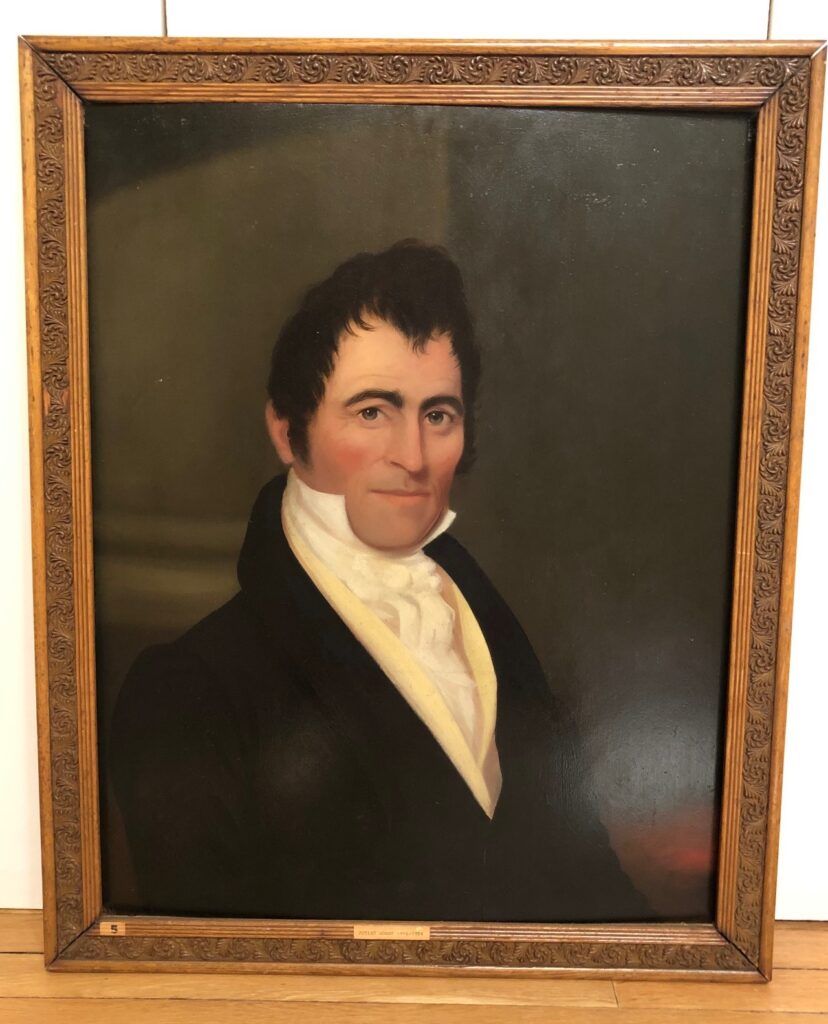

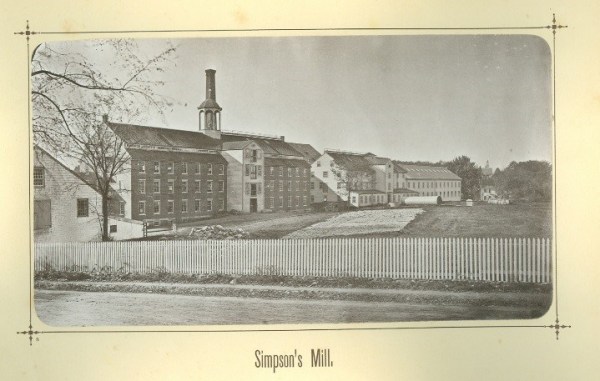

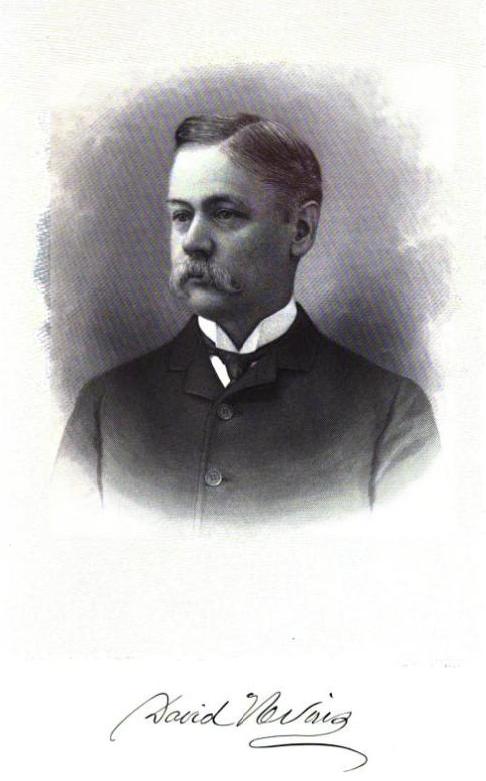

Our story begins in Methuen on July 30, 1839 with the birth of a son to David and Eliza (Coffin) Nevins. David Jr. was the first of two sons. His brother, Henry Coffin Nevins, was born four years later on January 10, 1843. David Sr. (1809-1881) was a successful businessman, banker, and textile mill owner. He owned Nevins & Co., a dry goods house located in Boston, the Pemberton Mills in Lawrence, and The City Exchange Banking Company of Boston. The City Exchange Banking Co. eventually merged with the other Nevins businesses and became the Nevins & Co. Bankers & Negotiators of Business with offices on Devonshire St.

After completing his education in Boston and Paris, David Jr. went to work with his father. He was employed on the banking side of his father’s business and managed the City Exchange Banking Company for a time. As his father aged, David, Jr. took a greater role in the running of these companies (Cutter 978). After their father’s death in 1881, David and his brother Henry inherited the family businesses. With the brothers at the helm, the Nevins’ concerns flourished.

In April 1862, David, Jr. married Harriet Francoeur Blackburn (1841-1929), the daughter of one of his father’s business associates. David and Harriet lived with her father, George Blackburn, at his home at 48 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston.

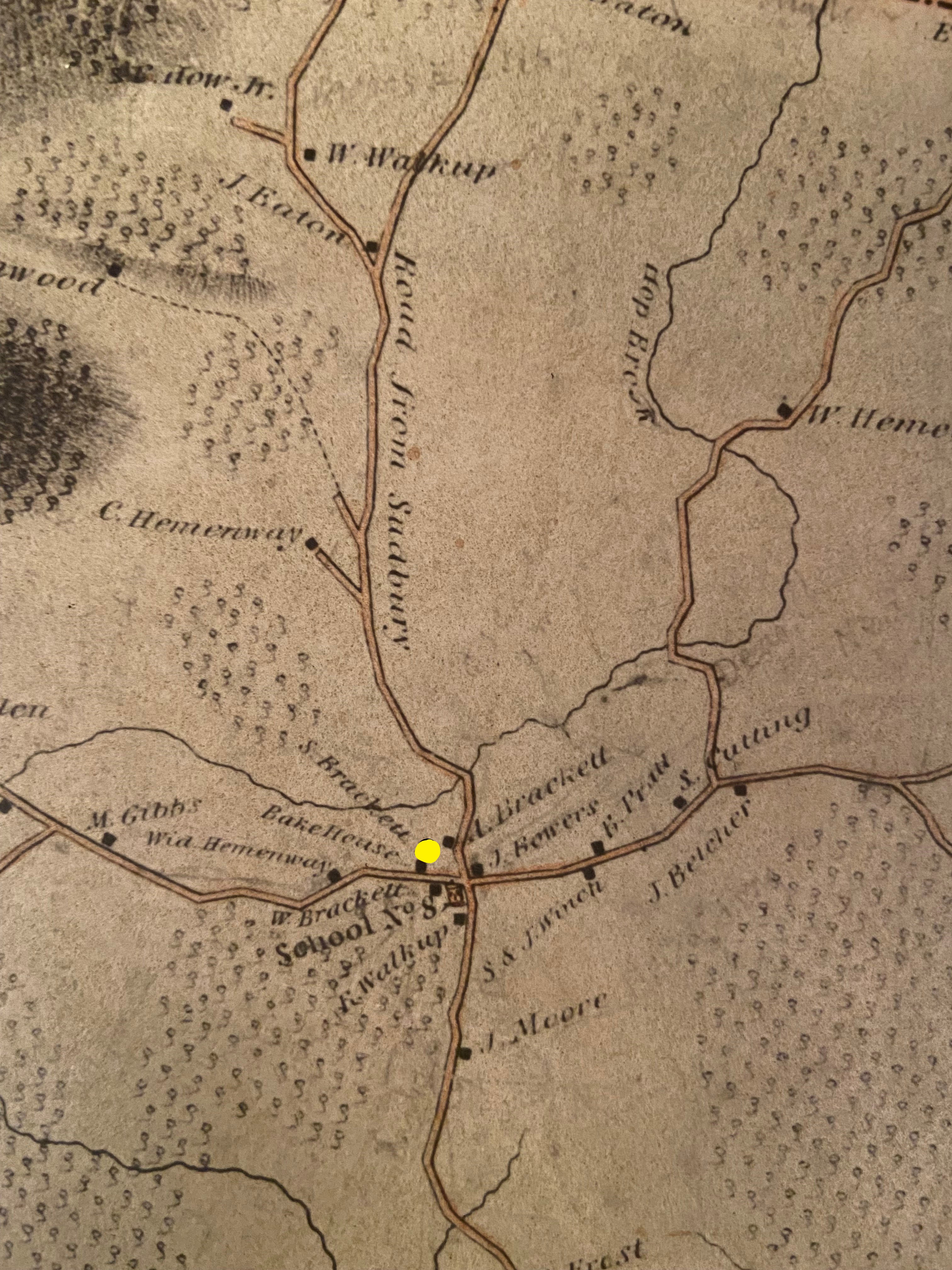

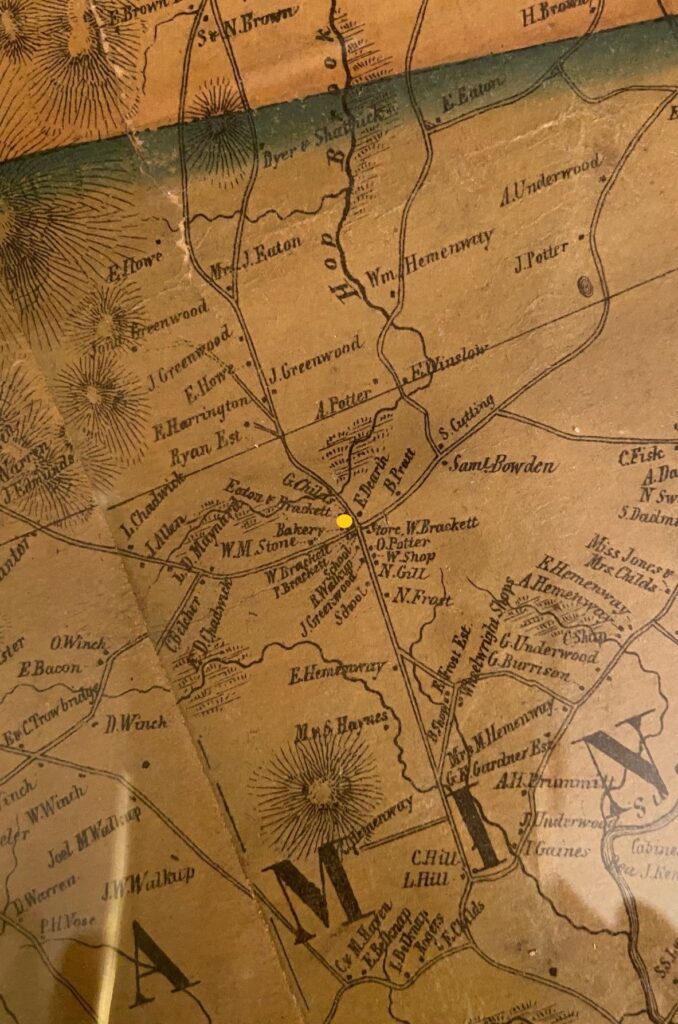

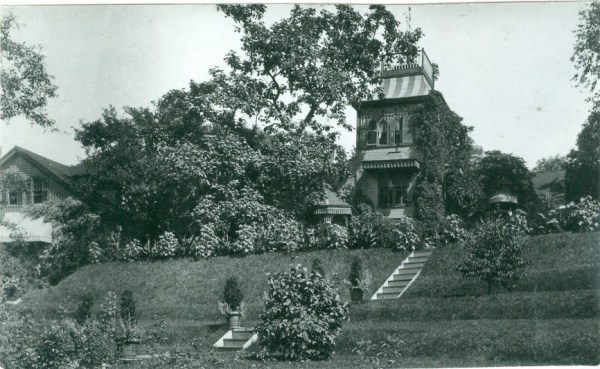

In the spring of 1870 the couple purchased a farm formerly owned by H. G. White, Esq. The property, near Park’s Corner in South Framingham, extended from Winter Street to Farm Pond. Hillside, as it was called, became the Nevins’ primary residence, where they spent eight months each year. For years, they also maintained a home at various locations in Boston for the winter season. In 1885, David bought the Hotel Tudor, an elegant apartment building on the corner of Beacon and Joy Streets in Boston. An apartment on the top floor became their permanent winter home.

After purchasing Hillside, David extensively remodeled and added to the house and farm buildings. Many modern features were added to the house including gas lighting and indoor plumbing. The gas for lighting was produced right on the Nevins’ property. Another innovation was the recycling of refuse from the house. The refuse from the plumbing was piped to a reservoir where it was then used to fertilize the fields. David had the cow stables remodeled to accommodate horses. A new stable and carriage house was built as well as a large house for the seven farmworkers who lived there in 1871 (Forbes).

By 1871, Hillside encompassed about 175 acres of land. Nevins employed a large number of landscapers to maintain the park-like grounds and gardens, and annually spent thousands of dollars on trees and plantings. He opened the estate’s grounds to the people of Framingham to visit or to take a drive through the scenic gardens. In 1897, Nevins had a nine hole golf course built on his land for the Framingham Golf Club. This was the first golf course in Framingham and it was called Pincushion Links (Herring 207). The course was located south of Hillside and beyond the Sudbury River in the area of current day Pincushion Road off of Winter and Fountain Streets. The following spring, he had a clubhouse constructed on the course.

Nevins, like so many of the men of his era, was a horse breeder. He raised many award winning stallions at Hillside, including perhaps his most famous, Bay Fearnaught. Bay Fearnaught was considered one of the best roadsters in New England at the time (Merwin 127). His stallions were exhibited at the annual South Middlesex Agricultural Society fair and other New England fairs, winning prizes in 1871, 1872 and 1876. David’s interest in horses went beyond breeding. In 1870, he served as the secretary in the Boston Trotting Association. He was a member of the Boston Driving and Athletic Organization, a group of Boston businessmen interested in the sport of turf racing. In 1879, David was the group’s vice-president. And to round out his animal related activities, in 1877, he was one of the directors of the MSPCA.

By the summer of 1898, David was in poor health. On the advice of his doctors, he and Harriet traveled abroad to the thermal baths at Bad Manheim to take advantage of the healing power of the mineral rich waters. Despite the baths and excellent care of his German physicians, his health continued to decline. On August 24, 1898, just six weeks after leaving America, David died of heart failure (“David Nevins” 6). His funeral took place in the parlor at Hillside on September 10, 1898.

Before the Nevins’ left for Germany, David completed his last will and testament. In it he left the house and possessions to his wife for use during her lifetime. Upon Harriet’s death, their daughter, Elise Nevins would be the beneficiary. If Elise died childless, the will provided that the personal property go to the Nevins Memorial in Methuen and the bequests be honored. The bequests granted $10,000 to the Home for the Aged in Framingham and $100,000 to the Town of Framingham for a new town hall. In 1954, Elise Nevins passed away without heirs. After the bequests were fulfilled, the residual of the estate was divided equally and given to twenty Massachusetts charities selected by the executors. Framingham Union Hospital was one of these (Framingham Union 1955).

And now you know why Nevins Hall is so named.

Facts

- Eliza Coffin Nevins was the daughter of Jared Coffin of Nantucket, one of the most successful ship owners during the island’s whaling days.

- “Methuen Duck Cloth” was manufactured by the Nevins’ and was used world-wide for sail cloth and tent for the tropics.

- David, Sr. was the co-owner of the Pemberton Mills when the north wall of the factory collapsed on January 11, 1860. Fire then consumed the building. A devastating industrial calamity in which 115 people were killed or missing and another 165 were injured. He rebuilt the mill adding many safety features (The Lawrence).

- The name Pincushion Links is credited to Mrs. Nevins. She thought that Merriam Hill topped with tall pine trees looked like a pincushion. The golf course was built near “Pincushion Hill.” (Herring 207)

- Framingham Golf Club was organized in the early 1890s. In the years following Nevins’ death, the club changed its name to the Framingham Country Club and acquired the William Temple estate on Gates Road.

- According to the 1880 Census, the Nevins’ adopted a son and a daughter after suffering two stillbirths in 1863 and 1865. Only their daughter Elise survived them.

Bibliography

“Autumn Products.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 20 Sept. 1877. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3009244525/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=7a198406. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“The Beacon Park Races.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 2 Sept. 1879. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3006600585/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=e0d82f57. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

City of Framingham. Website. https://www.framinghamma.gov/1052/Nevins-Hall. Accessed 17 Oct. 2022.

Cutter, William Richard. Genealogical and Personal Memoirs: Relating to the Families of Boston and Eastern Massachusetts. Lewis Historical Pub., 1908.

David Nevins. Boston Daily Advertiser, 25 Aug. 1898, p. 6. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3007059877/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=book mark-NCNP&xid=158f0a6d. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“David Nevins Resident of Framingham 30 Years Before Death in 1898.” Framingham News, 29 Apr. 1954.

“The Farmers’ Fairs.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 21 Sept. 1876. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3006555123/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=7b0e5cc4. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“FIFTH TO DIE.: CHARLES H. FRYE SUCCUMBS AT CITY HOSPITAL. ANOTHER IN THE LIST OF VICTIMS OF THE SHARON WRECK. HIS WIFE HAD ALSO LOST HER LIFE THERE. DOUBLE FUNERAL WILL BE HELD AT REVERE. BELLS TOLLED AND FLAGS AT HALF MAST IN THAT TOWN. BELLE TOLLED AT REVERE DIED FAR FROM HOME. DAVID NEVINS OF BOSTON AND SOUTH FRAMINGHAM, PASSES AWAY AT BAD MANHEIM, GER–WAS ABROAD SIX WEEKS. AT THE MARINE HOSPITAL SOLDIERS RECEIVING TREATMENT THERE ARE DOING FAIRLY WELL. OLIVETTE GOING TO FERANANDINA.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Aug 25, 1898, pp. 12. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/fifth-die/docview/498917569/se-2.

Forbes, A. A. “Framingham Farm Notes, No. 2.” New England Farmer. 25 Nov. 1871.

Herring, Stephen W. Framingham, an American Town. Framingham Historical Society, Framingham Tercentennial Commission, 2000.

The Lawrence Tragedy.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 12 Jan. 1860. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3009813383/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=d0358bd0. Accessed 20 Dec. 2022.

Merwin, Henry Child. Road, Track, and Stable. Little Brown & Co., 1892

“MORGAN–NEVINS.: BOSTONIAN WEDS METHUEN HEIRESS, AND GUESTS ARE ENTERTAINED IN TENTS ON SPACIOUS LAWN.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Jun 10, 1906, pp. 11. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/morgan-nevins/docview/500603436/se-2.

“Multiple Classified Advertisements.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 21 Apr. 1870. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3006458009/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=e900cd92. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“New England Fair.” Lowell Daily Citizen, 6 Sept. 1871. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3001749385/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=95d09fc6. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 17 Nov. 1887, p. 4. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3006793082/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=faad9284. Accessed 15 Nov. 2022.

“SOME LARGE PUBLIC BEQUESTS.: WILL OF DAVID NEVINS FILED FOR PROBATC- S1OO,000 FOR FRAMINGHAM TOWN HALL -METHUEN REMEMBERED.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Sep 15, 1898, pp. 8. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/some-large-public-bequests/docview/498937451/se-2.

“TOWN CLERK 46 YEARS.: BENJAMIN F. BAKER OF BROOKLINE DIES AT HIS HOME-ONE OF THE TOWN’S WELLKNOWN CITIZENS. EULOGIZED BY PASTORS. DAVID NEVINS CARRIED TO LAST RESTING PLACE. MOURNED BY MANY.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Sep 11, 1898, pp. 5. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/town-clerk-46-years/docview/498933679/se-2.