Framingham people cared passionately about their music. Temple tells us that Rev. Matthew Bridges, the second minister in town, held regular singing practice and trained seven members who had strong enough voices to start the psalms for the congregation to sing. The first choir was formed in 1768, but when stringed instruments were introduced to strengthen the voices some older members of the congregation were distressed. Used to the familiar psalm tunes of his youth one elderly gentleman, on hearing the first lines of William Billings’ “David the King,” cried out, “Hold, hold!” and left the meeting house noisily. In 1798 the town hired a singing master and used money from the alewife fishing at Cochituate Brook as the “singers fish privilege.”

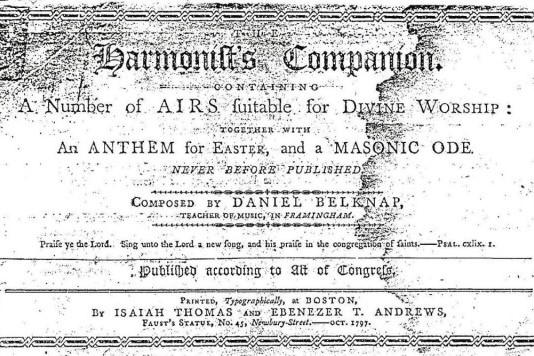

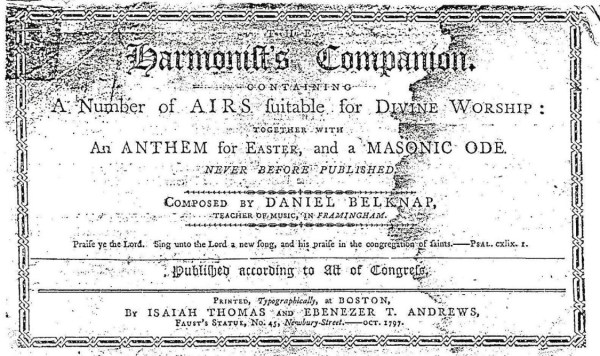

Daniel Belknap (1771 – 1815) grew up and went to common school in Framingham. He learned enough music to start his own singing school when he was only eighteen years old. His first songs were published in anthologies of religious tunes, but by 1797 he had brought out a tune book devoted entirely to his own work. In all he published four books of sacred music, the largest, The Village Companion, included fifty-six of his own compositions. He also published a secular “songster,” which included an instrumental piece, “Belknap’s March.”

His tunes are usually in four parts, with simple harmonies. The melody is often in the tenor voice, not the soprano, and in many cases the second half of the song is a “fuging tune,” starting with one voice followed by another and featuring some skipping dotted eighth notes. The titles of the tunes often have nothing to do with their words: “Framingham” is a meditation on the passion of Christ, as are “Holliston” and “Southborough.” “Hopkinton” is a call to repentance; “Keene,” a version of Psalm 11.

There is a “Funeral Ode” on the death of George Washington:

Deep resound the solemn strain,

Bid the breathing notes complain,

Say, Columbia’s hero’s fled,

Say, the world’s great chief is dead…

Belknap was a devoted Mason. In The Middlesex Songster there is “A Masonic Song:”

Before I became a Freemason,

I tho’t it some damnable thing,

I tho’t it was witchcraft & treason,

Some swore that the devil reign’d king.

But I thought to myself I would venture

Without any further delay,

With firm resolution to enter

To a Lodge, then hasten’d away.

And who would not be a free mason,

So happy and social are we;

To kings, dukes and lords we are brothers,

And in every Lodge we are free.

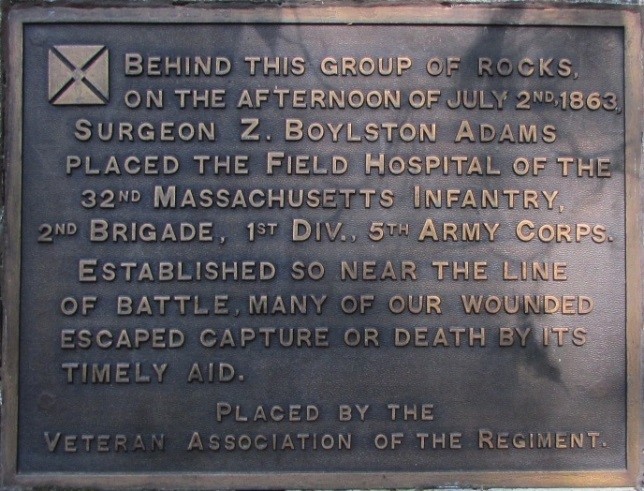

In the introduction to The Harmonist’s Companion, Belknap writes: “’A View of the Temple, A Masonic Ode,’ which appears in this work, was set to musick by particular desire, and performed by the author with several brethren of the fraternity, at the installation of Middlesex Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons, in Framingham in 1795.”

Belknap’s “Four Seasons,” unlike Vivaldi’s lively and descriptive concertos, consists of four brief and rather lugubrious hymns. The words start cheerfully enough with “Spring,” but lament the passing days in “Summer” and “Autumn,” and dread the “sullen vengeance” of the storm in “Winter.”

Belknap married Mary Parker of Carlisle and they had five children. The family moved to Providence in 1812 and Daniel died there three years later. His place among New England psalmodists is well established; one scholar even acclaims him as the most typical composer of them all.

Facts

The Middlesex Lodge of Masons met at the home of Jonathan Maynard, on the top floor of a house still standing on Pleasant Street.

Bibliography

Belknap, Daniel. The Collected Works, edited by David Warren Steel. Garland, 1991. Music of the New American Nation: Sacred Music from 1780-1820, Vol. 14.

Belknap, Daniel. The Harmonist’s Companion: Containing a Number of Airs suitable for Divine Worship, Together with an Anthem for Easter, and a Masonic Ode, composed by Daniel Belknap, Teacher of Music, in Framingham. Boston, Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T Andrews, 1797.

Belknap, Daniel. The Middlesex Songster, Containing a Collection of the Most Approved Songs now in Use. Dedham: Printed by H. Mann, 1809. {Photocopy of a copy at Brown University, p. 4-6.]

Cooke, Nym. “William Billings: Representative American Psalmodist?” The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, 7 (Spring 1996): 47-64. (quoted in Belknap. Collected Works, p. xxiii)

Parr, James L. and Kevin A. Swope. Framingham Legends & Lore. History Press, 2009. P. 63.

Temple, Josiah H. History of Framingham Massachusetts 1640-1885. Centennial year reprinting of the 1887 edition. New England History Press, in collaboration with the Framingham Historical & Natural History Society, 1988. P. 337-338.