Life in England had become unbearable under King Charles I due to heavy taxation and political and religious unrest. Like so many others, John, Bent, Sr. and his wife Martha, with their 5 small children, decided to emigrate to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in search of civil and spiritual freedom. In April 1638, they set sail out of Southampton, England on board the ship Confidence. At the time, John Bent, Jr. (baptized 1636-1717) was only two or three years old. The family settled in Sudbury, a small Puritan village, where John, Sr. farmed the land. In 1640, he became a member of the Puritan Church and was made a freeman. A freeman is one who can actively participate in town affairs.

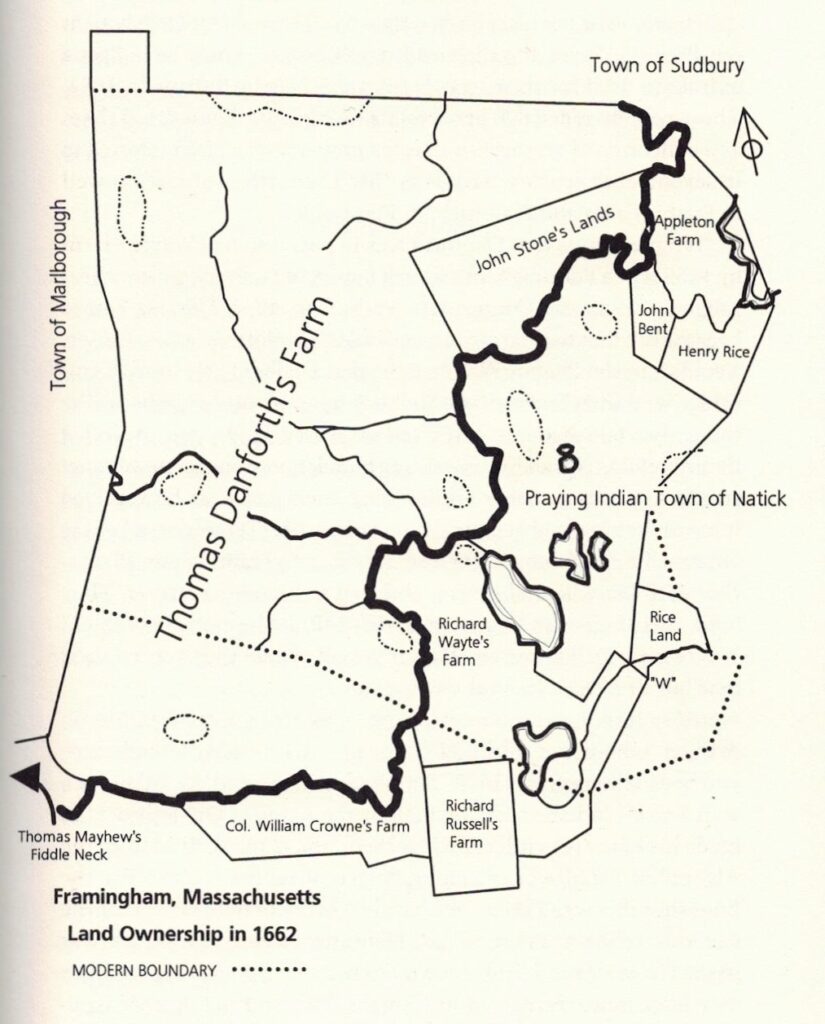

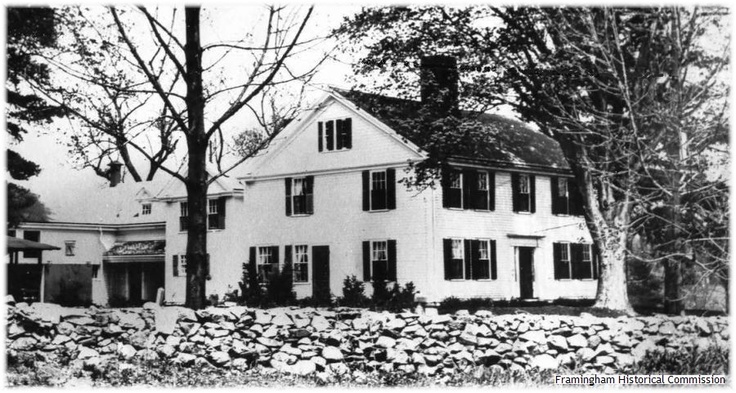

John, Jr. married Hannah Stone (1640-1689) of Cambridge on July 1, 1658. John and Hannah began married life in Sudbury where their daughter Hannah was born in 1661. In 1662, John, Jr. bought a tract of land from Henry Rice in Framingham. This land was “…near the fordway over the Cochituate Brook, on the west side of the old Connecticut Path … (Bent 15).” It was here in 1665 that he built one of the first houses in Framingham. Twenty-one years later, it appears that John was doing quite well as he bought an additional 60 acres adjoining his farm from Gookin and How.

After his wife’s death in 1689, John married Martha Rice (1657-ca.1717) on November 29th. She was the daughter of Matthew Rice of Framingham. They had two sons, John (1689-will dated 1754) and David (1691-1730).

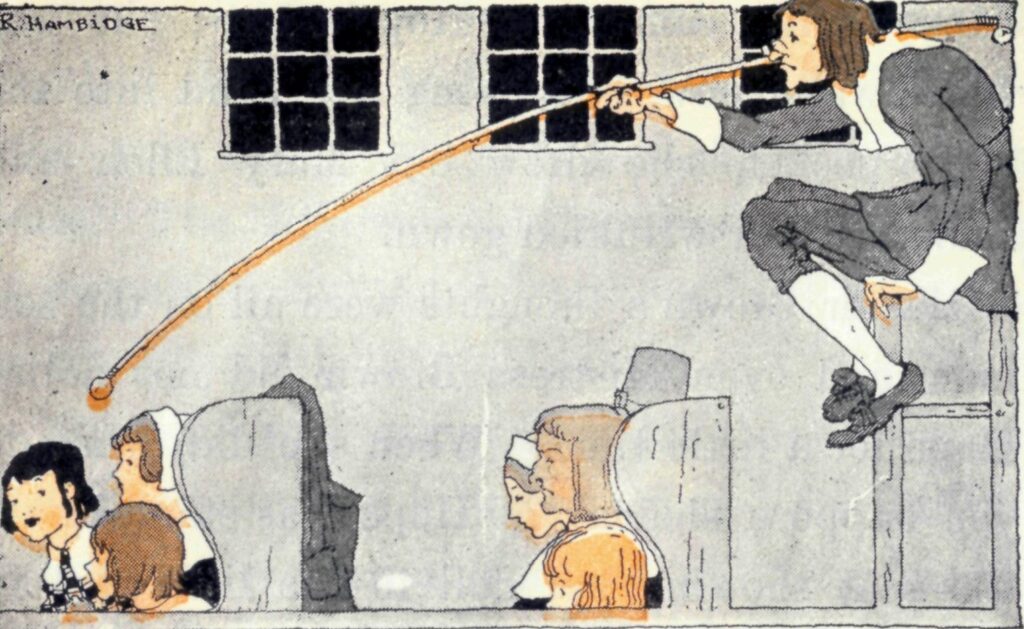

John, Jr. was an active member of the community. He headed the first petition for incorporation of Framingham in 1693. John’s petition failed. It would take several more attempts and another seven years before Framingham would become a self governing town. At Framingham’s second annual town meeting on March 3, 1701, John was assigned the job of tithingman, a very powerful position in Puritan towns. According to Merriam Webster’s Dictionary, a tithingman is “an elected local official having the functions of a peace officer in various American colonies (as Maryland and in New England) …” Their duties included “preserving order in church during divine service and enforcing the observance of the Sabbath.” During religious services, the tithingman carried a long staff with a heavy knob at one end and a feather or furry tail at the other. He was tasked with waking sleeping congregants and calming unruly children. Men and boys were tapped on the head with the knob while women were gently tickled with the feather or furry tail. Outside of church services, the tithingman was also charged with making sure that children received proper Bible study; keeping an eye out for drunks at the local taverns; and ensuring that everyone paid their fair share to the church.

John, Jr. lived a long life, dying at the age of eighty-two. In his will, dated August 1714, he left his estate to his two sons. It was noted that he had previously given his daughter, Hannah, her share.

Facts

- Siblings:

– Robert (baptized Jan. 10,1625-1648)

– William (baptized Oct. 24. 1626- died young)

– Peter (baptized Apr. 14, 1629-1678)

– Agnes (ca.1631-ca.1713)

– Joseph (baptized May 16,1641-?)

– Martha (ca.1643-1680) - The original location of John Bent, Jr.’s house was on the west side of Old Connecticut Path at the intersection with Speen Street. Around 1740, the house was moved to 1242 Concord St. where it still stands today. The Bent House is the longest standing residence in Framingham.

- Gookin and How: Samuel Gookin and Samuel How bought about 200 acres of land from the Natick Indians in the area known as Indian Head Hill. The wording of the agreement was a bit vague and Gookin and How took advantage of this loophole. In time, they claimed and sold off nearly 1,700 acres (Herring 28).

- John Bent, Jr was the third person to settle in Framingham. He followed John Stone in 1645, Saxonville, and Henry Rice in 1659, the area between Old Connecticut Path, Speen St. and Concord St.

Bibliography

Badertscher, Vera Marie. “John Bent Jr. , Tithingman of Framingham.” Ancestors in Aprons. Accessed 27 June 2020.

Bent, Allen Herbert. The Bent Family in America: Being Mainly a Genealogy of the Descendants of John Bent who Settled in Sudbury, Mass., in 1638, with Notes Upon the Family in England and Elsewhere. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=BnwTHw-t-d0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Accessed 27 June 2020.

Browne, Hetty S., Sarah Withers and W. K. Tate. The Child’s World, Third Reader. Johnson Publishing, 1917. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15170/15170-h/15170-h.htm#doll Accessed 27 June 2020.

Evans-Daly, Laurie and David C. Gordon. Framingham. Arcadia Publishing, 1997.

Herring, Stephen. Framingham: An American Town. Framingham Historical Society, The Framingham Tercentennial Commission, 2000.

MacDonald, Jan. “History Haunts Framingham House Tour.” MetroWest Daily News. 13 May 2009.

“Tithingman.” Dictionary by Merriam Webster. Merriam-Webster.com. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tithingman Accessed 27 June 2020.

“THE TITHINGMAN AND HIS LONG STAFF.” New York Times (1923-Current file), Jun 24, 1928, pp. 1. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/docview/104518553?accountid=9675. Accessed 27 June 2020.