Margaret E. Knight (1838 – 1914), a nineteenth century inventor, was born on February 14, 1838 in York, Maine to James and Hannah (Teal) Knight. She had two older brothers, Charlie and Jim. Mattie (as she liked to be called) was young when her father died. In order to support the family after her husband’s death, Hannah Knight moved her family to Manchester, New Hampshire where she and her sons found work in the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company (textile mills).

Inventing had always been a part of Mattie’s life. As a young girl, she was interested in machines and how they worked. Her favorite “toys” were her woodworking tools, which she used to make and improve toys for her brothers and their friends. One day when twelve-year-old Mattie was delivering lunch to her brother at the mill, she witnessed a worker get injured when a metal tipped shuttle flew off one of the looms (weaving machines). Mattie knew that there had to be a way to improve this machine and make it safer. After much thought and sketching, she devised a metal guard that would stop a shuttle from flying off the loom when the thread broke. The mill owner installed her guards on all of his looms.

After completing elementary school in Manchester, Mattie went to work to help support the family. She worked in the textile mills, in engraving studios, and she even worked repairing houses. She loved learning how to use new and different tools.

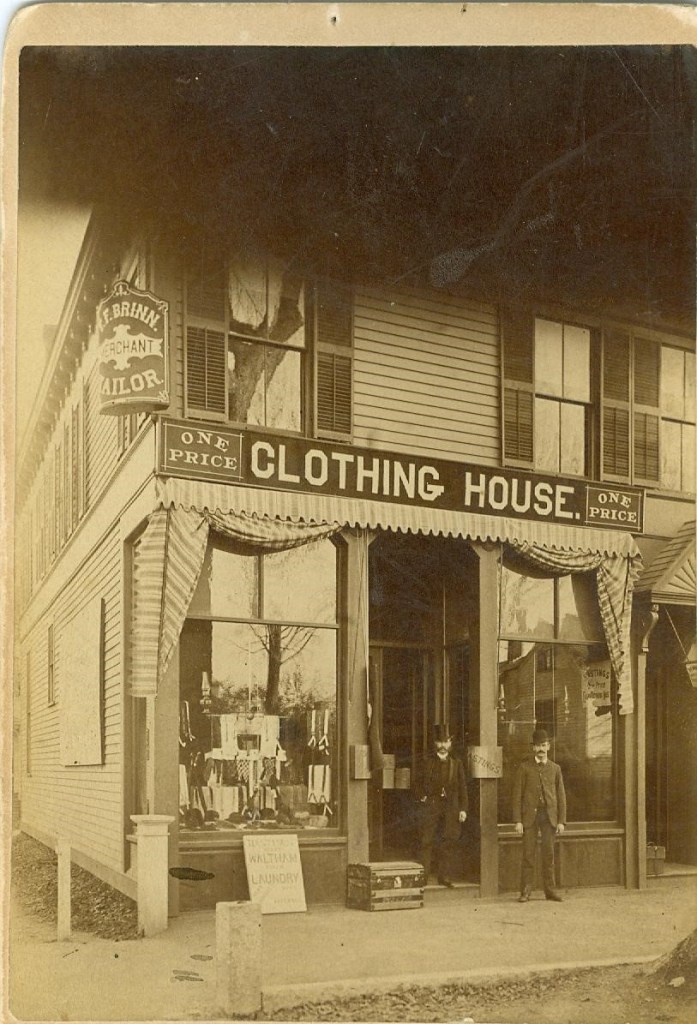

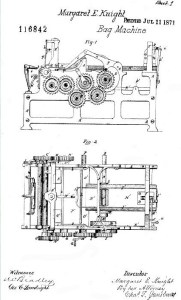

In 1867 at the age of eighteen, Mattie moved to Springfield, Massachusetts to work at the Columbia Paper Bag Company as a bag bundler. The bundler prepared the completed paper bags for shipment by collecting, stacking, and bundling them. These bags were flat envelope style bags and were not good for carrying bulky items such as groceries. Square bottom bags, good for larger items, had to be made by hand and were much more expensive. Mattie spent two years designing a machine to make square bottom bags. When her machine design was complete, she hired a machinist to make her machine out of iron and then another machinist to make improvements to it.

In February 1870, when she applied to the United States government for a patent on her machine, she discovered that someone else had already submitted her plans and had received the patent. Charles Annan, a businessman who had visited the machine shop several times and learned all about her machine, built his own and got the patent. Mattie hired a lawyer, gathered her diary, patterns, sketches, records, and witnesses and went to Washington, D.C. to prove that it was her invention and not Annan’s. She won her court case and was given her patent on July 11, 1871 – Patent number 116,842.

With patent in hand, Mattie moved to Hartford, Connecticut and started the Eastern Paper Bag Company. These machine-made square bottom paper bags became the most popular way to bundle and carry goods, and were used by large and famous department stores such as Macy’s and Lord and Taylor’s in New York City.

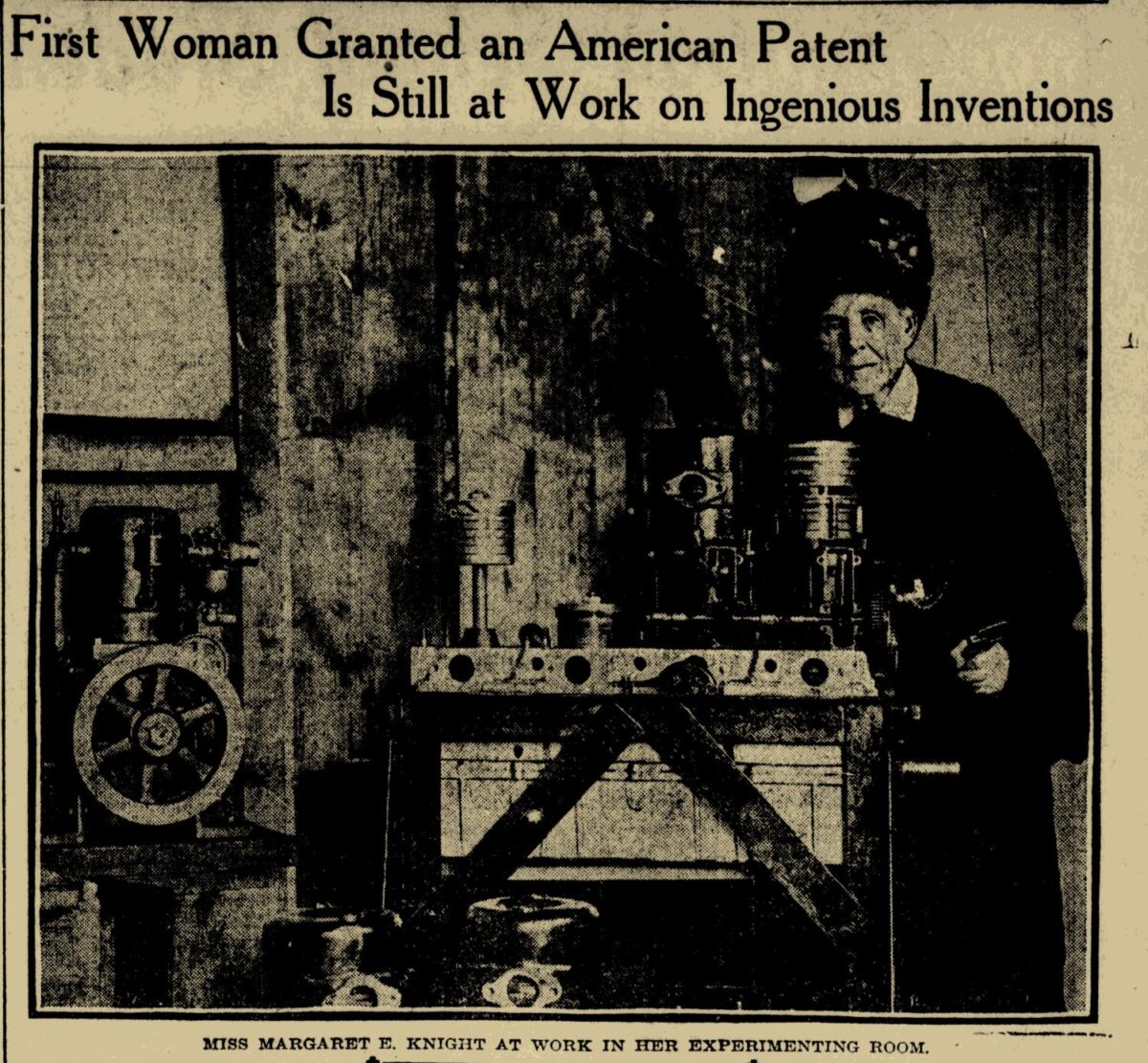

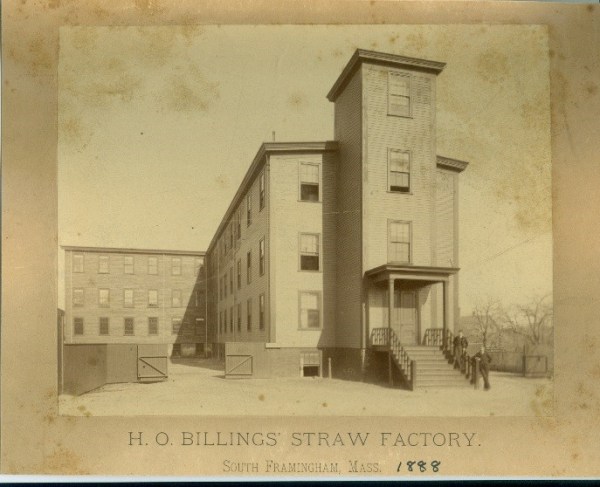

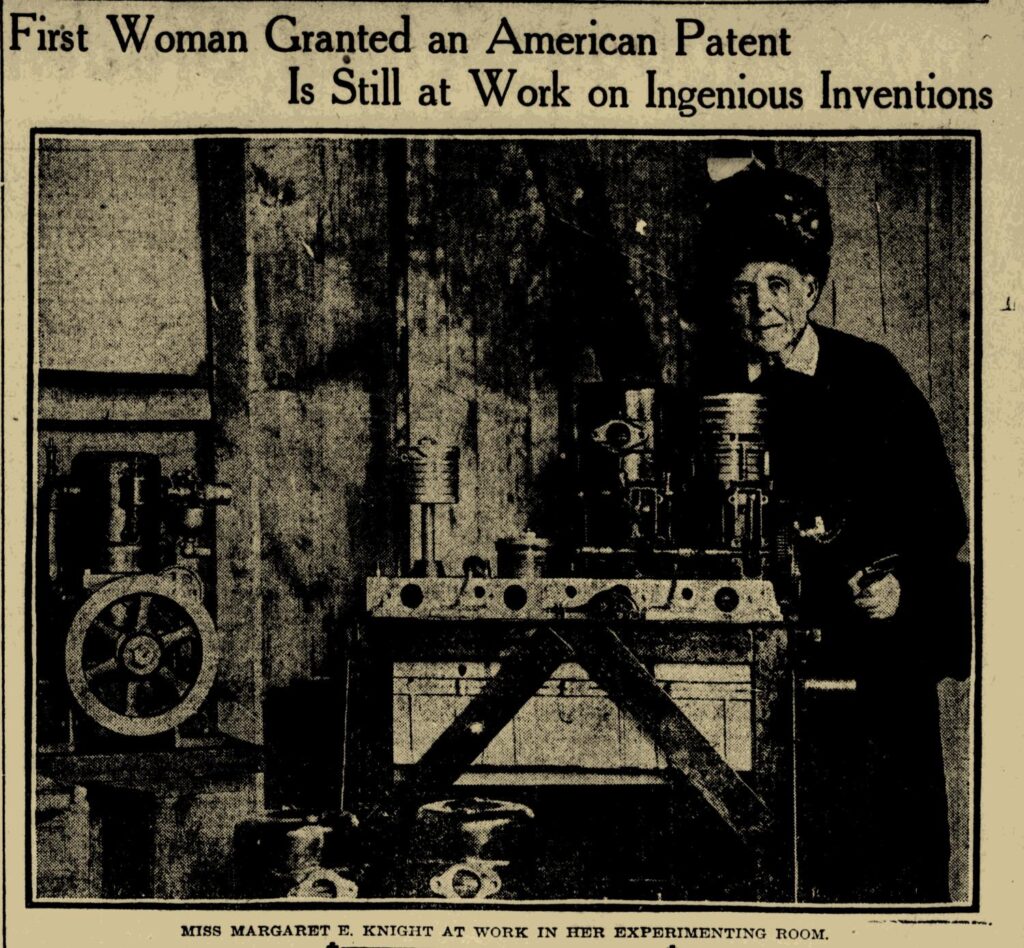

In the 1880s, Margaret Knight moved again, this time to Ashland and then South Framingham, Massachusetts. She set up a laboratory in Boston where she continued to invent. During the 1880s and 1890s, she focused her inventing on household items, such as a dress and skirt shield (1883), a clasp for robes (1884), a barbecue spit for cooking meat (1885), machines used in shoemaking (1885), a sewing machine reel (1894), and a window frame and sash (1894). In the last decade of her life, she became very interested in automobiles and worked on making devices for their rotary engines.

Mattie lived the last twenty-five years of her life in a house, called Curry Cottage, in South Framingham. This house still stands at 287 Hollis Street. She died at the Framingham Hospital of pneumonia and gallstones on October 12, 1914 at the age of seventy-six. She is buried in Newton, Massachusetts.

Further Reading

“American Artifacts preview: 19th Century Inventor Margaret Knight.” American HistoryTV, C-Span3. YouTube. posted Sept. 12, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YM0ewutCMQ Accessed 27 Apr. 2017.

Michelle. “Learning from InvENtors: Margaret Knight.” Edison Nation blog, posted Jan. 5, 2017, http://blog.edisonnation.com/2017/01/learning-from-inventors-margaret-knight/ Accessed 30 Apr. 2017

Petroski, Henry. “The Evolution of the Grocery Bag.” American Scholar, vol. 72, no.4, Autumn 2003, p. 99+ www.teacherpage.com/cubslibrary/docs.evolution_of_the_grocery_bag.doc Accessed 30 Apr. 2017.

Bibliography

Blashfield, Jean F. Women Inventors 1. Capstone Press, 1996.

Brill, Marlene Brill. Margaret Knight, Girl Inventor. Millbrook Press, 2001.

“Margaret E. Knight.” Britannica School, Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 Feb. 2017. school.eb.com/levels/high/article/Margaret-E-Knight/125831 Accessed 26 Apr. 2017.

“Margaret E. Knight.” Encyclopedia of World Biography, vol. 35, Gale, 2015. Biography in Context, libraries.state.ma.us/logingwurl=http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K1631010308/BIC1?u=fp l&xid=7db94b2a Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

“Margaret Knight.” Notable Women Scientists, Gale, 2000. Biography in Context, libraries.state.ma.us/login?gwurl=http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K1668000218/BIC1?u=fpl&xid=dc7bc13a Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

“Margaret E. Knight.” Paper Industry International Hall of Fame, Inc., 2008. http://www.women-inventors.com/Margaret-Knight.asp Accessed 27 Apr. 2017.

“Margaret E. Knight.” World of Invention, Gale, 2006. Biography in Context, libraries.state.ma.us/login?gwurl=http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K1647000207/BIC1?u=fpl&xid=053b5050 Accessed 20 Apr. 2017.

McCully, Emily Arnold. Marvelous Mattie: How Margaret E. Knight became an Inventor. Farrar Straus Giroux, 2006.

Thimmesh, Catherine. Girls Think of Everything: Stories of Ingenious Inventions by Women. Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000.