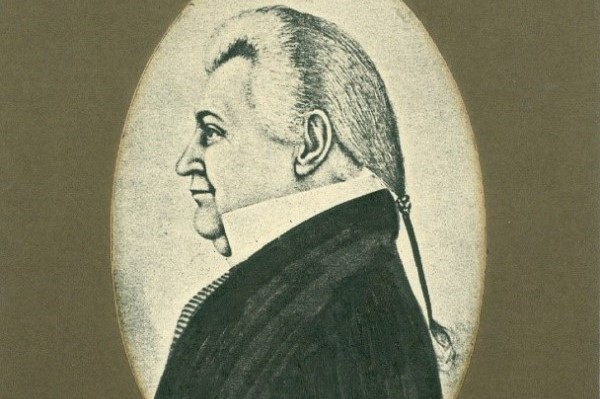

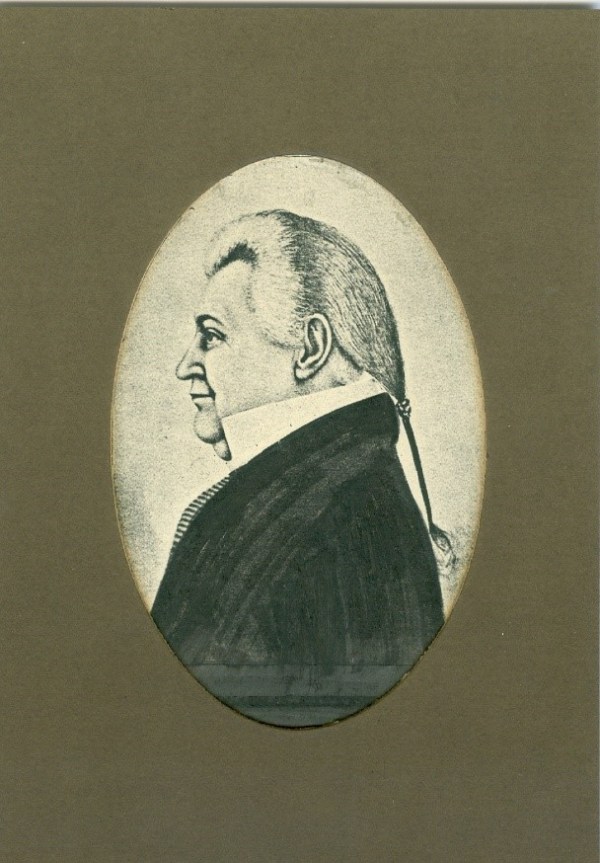

The Rev. John Swift (c.1678 – 1745) was Framingham’s first official minister. Very little is known of Swift’s childhood and adolescence. He was born and raised in Milton, Massachusetts and graduated from Harvard in 1697. Two years after his graduation, he came to Framingham to preach.

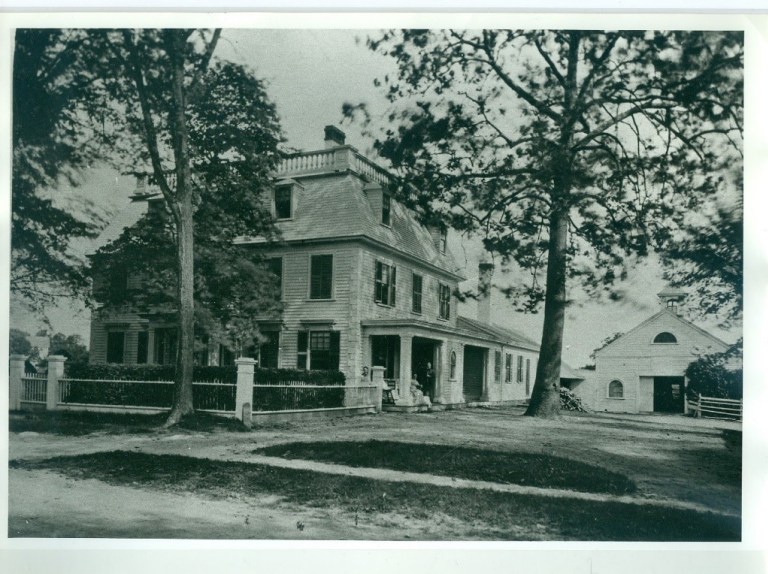

Framingham was incorporated as a town in 1700. At its second town meeting on August 21, 1700, Swift was asked to stay on as the town’s first resident minister. As payment for his services, he received 100 pounds toward the cost of building a house in the area of present day Swift Road and Maple Street, one hundred acres of land, 10 acres of meadows on Maple Street. Rev. Swift also received a yearly salary of sixty pounds. He held religious services in the town’s meetinghouse, a two story barn-like building measuring forty feet by thirty feet built in 1698 on Bare Hill. Thomas Danforth had set aside this land in the center of Framingham’s six settlements for ministerial use.

With Rev. Swift in the pulpit, the first official church in Framingham was established in 1701 by eighteen families. The Framingham Church was associated with the Puritan religion and all citizens of the town were taxed to support it and the minister. In 1735, a second meetinghouse was built in the center of town in the area of Vernon Street and Edgell Road. It was larger than the first measuring fifty five feet by forty two feet and three stories high.

Rev. Swift not only ministered to his parishioners, but according to entries in his diaries, he served on nineteen ecclesiastical councils over an eight year period. Annually, as was the custom of the time, he met with the young people in the congregation to publicly quiz them on their catechism.

Rev. Swift married Sarah Tileson (1674-1747) on December 16, 1701 in Dorchester, Massachusetts and they had six children, five girls and one boy. Following in his father’s footsteps John Swift, Jr. served as minister in Acton, Massachusetts after graduating from Harvard College. From 1733 to 1734, he worked as a school master in Framingham.

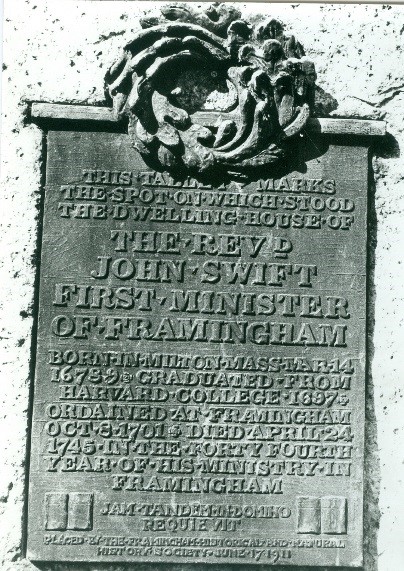

For forty-four years John Swift served as minister to Framingham. After a long illness, he died on April 24, 1745 and was buried in the Old Burying Ground on Main Street. His obituary in the Boston Evening Post, dated May 13, 1745, described him as pious, diligent, intelligent, faithful and prudent.

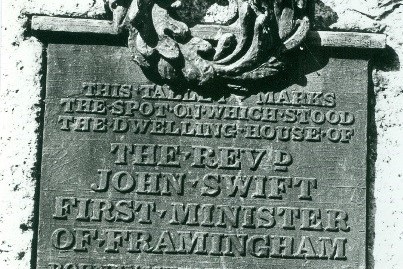

On June 17, 1911, The Framingham Historical and Natural History Society erected a granite marker with bronze plaque to mark the site of Rev. John Swift’s home on Maple Street.

Facts

Abel Benson was the grandson of Rev. Swift’s slave Nero.

Framingham settlements in 1700s: Saxonville, Nobscot, Salem End, Pratt’s Plain, Stone’s End, and Sherborn Row.

Members of the first church in Framingham: Henry Rice, Daniel Rice, Jonathan Hemingway, Thomas Drury, John Stow, Simon Mellen, Peter Cloise, Benjamin Bridges, Caleb Bridges, Thomas Mellen, Benjamin Nurse, Samuel Winch, John Haven, Isaac Bowen, Stephen Jennings, Nathaniel Haven, Thomas Frost.

Framingham’s first official road was built to connect the Meeting House to the minister’s home.

First meeting house site is within the Old Burying Ground on Main Street

Rev. Swift was ordained October 8, 1701

Bibliography

Barber, John Warner. Historical Collections Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town Every in Massachusetts with Geographical Descriptions. Warren Lazell, 1844. https://archive.org/stream/historicalcolle00barbuoft#page/386/mode/2up/search/framingham Accessed 01 Aug. 2017.

Dewar, Martha E., ed. Framingham Historical Reflections. Framingham 275th Anniversary Committee, 1974.

Herring, Stephen. Framingham: An American Town. Framingham Historical Society, The Framingham Tercentennial Commission, 2000.

“History of the Plymouth Church.” The Plymouth Church in Framingham. https://sites.google.com/site/plymouthwebsite/whoarewe/history Accessed 05 July 2017.

Temple, Josiah H. History of Framingham, Massachusetts, 1640-1885. A special Centennial year reprinting of the 1887 edition, New England History Press, 1988.