In nineteenth century America, the exhibition of so-called “freaks of nature” was a popular and accepted form of entertainment. These exhibits were promoted as being morally uplifting and educational (Fordham 208). Audiences included not only the curious from all social classes, but also physicians and scientists interested in studying human anomalies. There were different kinds of exhibitions: small traveling shows, permanent museums, and sideshows attached to traveling circuses.

There were three kinds of “human curiosities” found in the exhibitions: natural, man-made, and people with unusual talents or skills (Fordham 211). Natural curiosities included conjoined twins, oversize or under-size humans, those with mental or behavioral differences, and armless or legless humans. Man-made curiosities were people who had altered their bodies, such as those who were covered with tattoos, or the giraffe-necked women. The third category featured sword swallowers, fire-eaters, and contortionists!

Though these shows are credited with providing employment to many who would have otherwise been ostracized from society and impoverished, they were also rife with examples of exploitation, racism, and ableism. As such, the stories of the individuals who spent their lives starring in these shows are widely varied, with some finding their stardom to be enriching and empowering, while others were actively disenfranchised and abused. The story of Dollie Dutton is, sadly, illustrative of the story of many other sideshow stars, as well as of the later vaudeville and motion picture child stars who followed her.

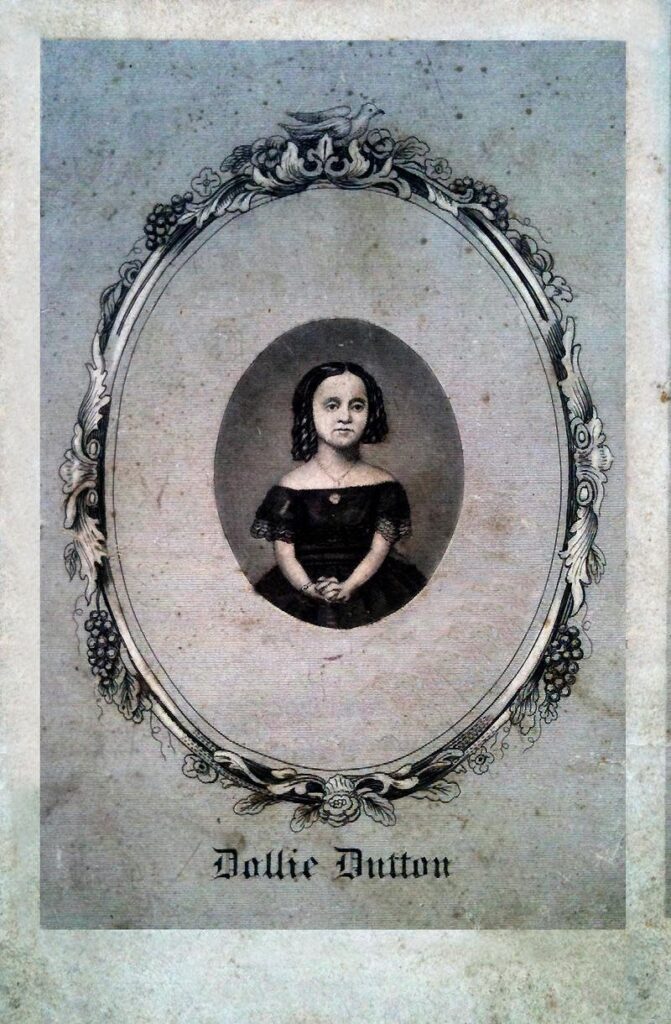

On June 28, 1853 in Framingham, a little girl was born destined for national fame as a “natural curiosity”. Alice Marie Dutton (1853-1890), daughter of David and Ellen (Davis) Dutton, was a perfectly formed infant weighing only two and a half pounds at birth. Her small birth weight was a harbinger of her future stature. For you see, Alice suffered from proportional dwarfism. She was literally a miniature human being. When she was seven years old, a newspaper article described her as:

“Tiny as the smallest fairy, she is also as beautifully formed; the delicately rounded limbs, fair skin, waving ringlets, and large and lustrous eyes, making her stand forth a living impersonation of the ‘Queen of the Fairies’ (“Fairy”).”

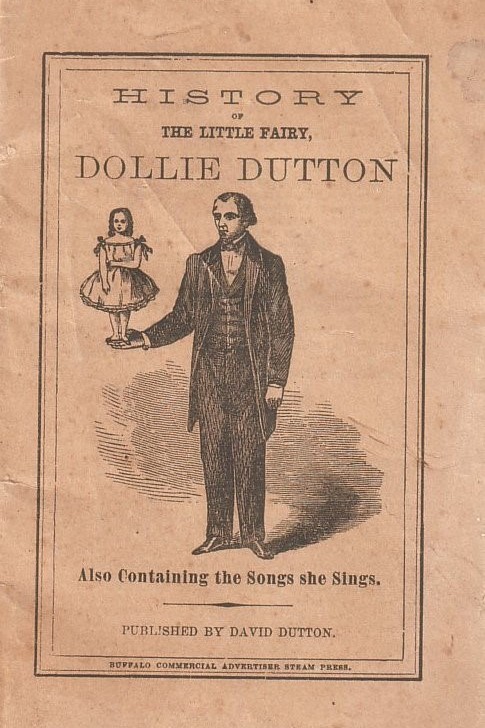

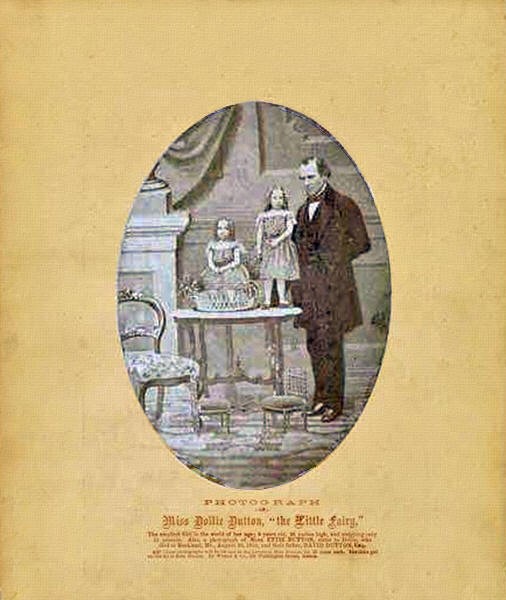

People from all over the Dutton’s neighborhood and beyond came to see this very special little baby. When Alice, who was called Dollie, was only six months old, her father decided to capitalize on his daughter’s uniqueness and the public’s curiosity. He took Dollie into Boston and exhibited her in a tent at the Public Garden. After doing this for eighteen months, another exhibitor convinced Dollie’s father to show her for a fee at the Boston Music Hall. This was the start of her career in the entertainment business. Dollie’s older sister Etta, was also a little person. Dollie and Etta were exhibited together during this first stage of her career.

In 1857, Dollie’s aunt, Mrs. Sarah P. Davis of Salem, Massachusetts, assumed the management of her career from her father. Sources don’t indicate why this change in her management was enacted.

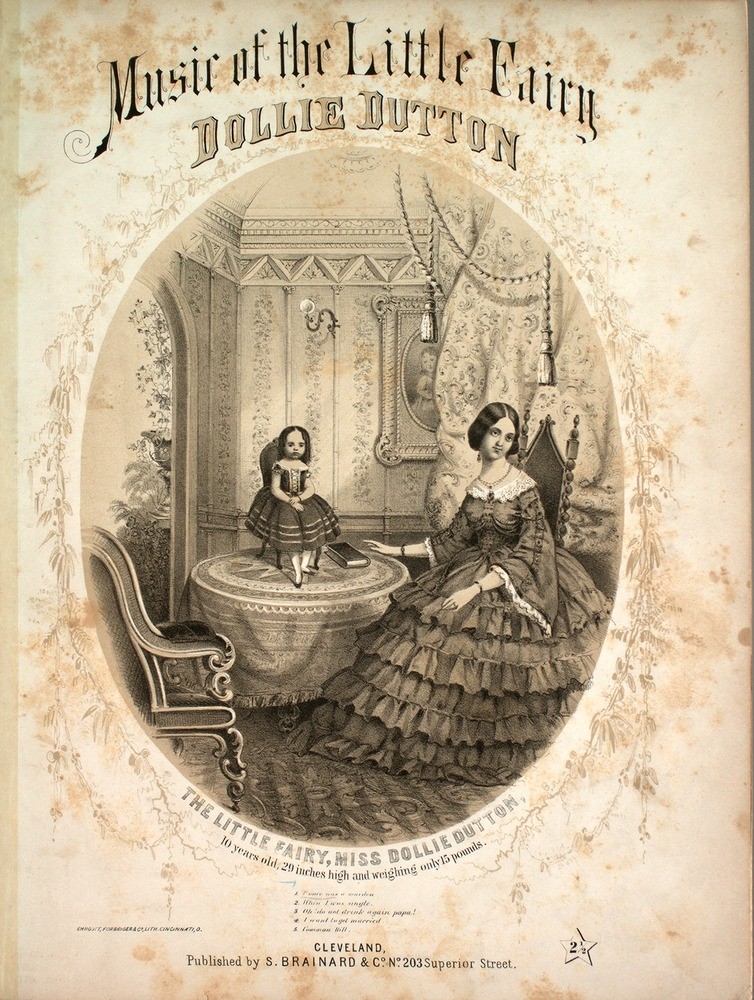

To enhance Dollie’s performances, Aunt Sarah arranged for her to take dance lessons from Sylvanus Kneeland Jr., a popular instructor in Boston (Sansonetti). As her manager, Sarah accompanied Dollie as she travelled around the country to performance venues.

Etta’s death at age ten in 1859 marked the beginning of Dollie’s solo career. Despite what was likely the traumatic loss of her sister, Dollie — weighing thirteen pounds and standing two feet tall — charmed audiences in almost every state in the Union and Canada. In 1860, when Dollie was only seven years old, she entertained five hundred thousand people at her levees in New Orleans, Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Burlington, Vermont, Boston, and New York City. During her six week stay in Boston, forty thousand tickets were sold (“History”). With admission to one of her levees, costing fifteen cents for adults and ten cents for children, it was estimated that she earned about fifty thousand dollars that year (“Varieties”). It is not clear whether Dollie herself actually benefited from her earnings. Dollie was one of the most renowned child entertainers of her day, and was as big a draw as General Tom Thumb!

When touring, Dollie would perform two one hour long levees each day, one in the afternoon and the other in the evening. In each performance she would sing solos, dance the polka, and perform alongside other entertainers and musicians. These entertainers included other little people such as Miss Sarah Belton, a singer, and Miss Wilhelmina Kappas, a German dancer. To highlight her smallness, she would stand beside either a “giant” like F. Decker, the Ossian Giant Boy who was seven feet tall and weighed 300 pounds, or an ordinary sized child her own age. Dollie did have some singing talent as she was praised in the press for her clear, distinct voice (“Dollie Dutton”). There was nothing more spectacular than Dollie’s entrance into the room. Sometimes she would pop up out of a little basket used for carrying flowers. Other times, she would be carried in while standing in the palm of her father’s or a manager’s hand. In addition to her levees, Dollie also toured the United States with General Tom Thumb’s Troupe.

Dollie retired from public life when she was eighteen years old. It was reported that she was difficult to manage, and sometimes would refuse to go on stage. When this happened, her manager was required to give refunds to everyone in attendance (“Difficult”). Though the sources don’t speak to Dollie’s perspective, it is little surprise that she began to assert herself as she finally reached adulthood. One can only guess that she had tired of a performer’s life on the road, a career she had not chosen for herself.

On June 15, 1874 she married Benjamin Franklin Sawin (1856-1905) in Natick, Massachusetts. Benjamin was of normal stature. The couple had one child who survived only a few hours. The marriage did not last. When Dollie left Benjamin, she moved in with her family in Natick.

Dolly was committed to Worcester Insane Asylum in 1882 suffering from dementia caused by domestic troubles (“Multiple” 1882). What these “domestic troubles” were is not clearly stated in the historical record. In that era, however, it was not unusual for “difficult” women to be hospitalized or incarcerated. She spent the rest of her life in the Asylum. She died on June 6, 1890 of dementia and epilepsy. Dollie’s passing was reported in newspapers all across the United States. Alice Marie “Dollie” Dutton Sawin is buried in the Dutton Family plot in The Main Street Cemetery, Hudson, Massachusetts.

Facts

- Siblings: George William, 1848-1935; Jeanette (known as Etta), 1849-1859; Ellen Frances, 1851-1858. George and Ellen were normal in stature.

- Parents: David Dutton, 1825-1888, a shoemaker; Ellen Davis Dutton, 1823-1900. Married April 30, 1846 (Wayland 69)

- Levee: a formal reception of visitors or guests.

- Dollie’s age, height and weight were often inaccurately reported to portray her as older and smaller than she actually was for promotional purposes. Her year of birth appears as 1853 (Massachusetts birth records) and 1855 (Find a Grave). Her full adult height is reported ranging from 22 to 29 inches.

- Stage name: The Little Fairy.

Bibliography

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. University of Chicago Press, 1988.

“Difficult to Manage.” The Hopewell Herald, 29 Nov. 1882. Ancestry.com.

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8599/?name=dollie_dutton&keyword=dollie+dutton. Accessed 14 Oct. 2020.

“Dollie Dutton.” Cleveland Morning Leader, 21 Nov. 1860. Newspapers.com.

https://www.newspapers.com/image/75696082 Accessed 13 Oct. 2020.

“Dollie Dutton Dead.” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, 12 Jan. 1890, p. 5. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3003062585/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=cb5f54d4 Accessed 1 Sept. 2020.

“Dollie Dutton’s Levees, at the Assembly Buildings, are every day and evening thronged with many hundreds of intelligent persons, who manifest the greatest interest in the little creature.” North American, 8 May 1860. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3009291828/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=86e95aa3 Accessed 1 Sept. 2020.

Dutton, David. History of The Little Fairy, Dollie Dutton. David Dutton, [1859?].

“Fairy Legends Becoming Verified.” Cleveland Daily Herald, 24 Nov. 1860. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3005091759/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=bc7ec864 Accessed 1 Sept. 2020.

Fordham, B. A. “Dangerous Bodies: Freak Shows, Expression, and Exploitation.” UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 14(2). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1g32z0dx Accessed 10 Oct. 2020.

“Freak show.” Britannica Library, Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 Nov. 2014.

library.eb.com/levels/referencecenter/article/freak-show/609347. Accessed 13 Oct. 2020.

“History of the Little Fairy,” Miss Dollie Dutton.” Burlington Weekly Sentinel 28 Sept, 1860. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=18277690&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjM2NTE2NTU1OSwiaWF0IjoxNjAyNjEwMjYwLCJleHAiOjE2MDI2OTY2NjB9.KyynZVuXMe59XslTFCxodRMOXhg9YslSjauvPYc9eIY Accessed 13 Oct. 2020.

In General.” Boston Daily Advertiser, 21 Nov. 1882, p. 2. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3006665024/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=a69f50cf. Accessed 27 Oct. 2020.

“The Little Fairy,’ Miss Dollie Dutton.” Vermont Patriot and State Gazette, 6 Oct. 1860. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3008128629/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=b958ed02 Accessed 9 Oct. 2020.

“Multiple Classified Advertisements.” Cleveland Daily Herald, 17 Nov. 1860. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3005091288/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=9fe3466 . Accessed 9 Oct. 2020.

“Multiple News Items.” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, 18 Nov. 1882, p. 8. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3002956263/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=875010cd Accessed 1 Sept. 2020.

Robinson, John. “Little Folks on the Midway: Dollie Dutton.” Sideshow World. http://www.sideshowworld.com/43-Little-Folks/2014/Dollie-Dutton/Little-Fairy.html. Accessed 29 Aug. 2020.

Sansonetti, Anthony. “Dollie Dutton.” Ambassadors of Empire. http://childperformers.ca/dollie-dutton/ Accessed 29 Aug. 2020.

“Says Smallest Woman in the World Framingham’s Dollie Dutton.” Framingham News. 9 July 1953.

“Varieties.” Cincinnati Daily Press, 28 July, 1860. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/186746232 Accessed 13 Oct. 2020.

Wayland, Mass. Vital Records of Wayland, Massachusetts to the Year 1850. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1910. Internet Archives. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofwa00wayl Accessed 31 Oct. 2020.

Well Spring Boston. “Local and Maine News.” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, 6 Aug. 1859. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/apps/doc/GT3007219930/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=NCNP&xid=cf7193ac Accessed 1 Sept. 2020.